After the success of The Amazing Maurice And His Educated Rodents (2001) it was inevitable that Terry Pratchett would turn his hand to another Discworld novel for children. Although, given his turnover of books at this time, Maurice could have just been the advance guard for the Tiffany Aching novels that seemed to dominate the Discworld novels in its last decade or so.

So just who are The Wee Free Men?

We first met the Nac Mac Feegles all the way back in Carpe Jugulum (1998). In that book we met a horde of them who were driven out of their home territory by the Magpyr vampire clan. They soon settled in Lancre and we seemed to hear no more from them.

However, there was another branch of the extended Feegle clan that settled a little way from Lancre in a region known as The Chalk. Here they had lived peacefully, stealing the occasional sheep for food, terrorising small animals and generally staying out of the way of the lady referred to as “the hag o’ the hills,” Granny Aching, a shepherdess who was a witch in all but name.

But Granny Aching has passed away, leaving a grieving family; specifically – for our purposes, at least – her granddaughter Tiffany, who has received enough education (most recently from travelling witch-spotter, Miss Tick) to know that she isn’t really cut out for an ordinary life in the Chalk.

One day, Tiffany meets a monster called a Jenny Greenteeth, which she promptly knocks out with a frying pan (after baiting the trap with her younger brother Wentworth). This brings her to the attention of Rob anybody, the leader of the local clan of Nac Mac Feegles. He decrees that Tiffany is perfect to become their “new hag” in the absence of Granny Aching, and with the impending death of the Kelda, witch and literal mother of his entire clan. He sets out to win Tiffany over. Tiffany is unsure of this whole new world that she is entering into, however, but becomes more resigned to the idea after Wentworth is kidnapped by the Queen of the Elves (who clearly hasn’t learned anything since her last appearance in Lords And Ladies) who also kidnapped Roland, the son of the local baron, a year ago. So Tiffany has to enter Fairyland, manage two rescues and get herself home safely as well…

There’s a lot to discuss with this novel, so I’m going to start with the biggest idea: the notion of landscape and how we hold to particular places and the hold they have over us.

In The Chalk, there aren’t many witches because the land isn’t solid enough… or something like that.

As Miss Tick says,

“I can do magic on honest soil, and rock is always fine, and I’m not too bad on clay, even… but chalk’s neither one thing nor the other! I’m very sensitive to geology, you know.“

Tiffany, however, has lived on the Chalk her whole life and is quite attuned to how the landscape works. This is a theme that will continue to grow during the rest of the Tiffany books, by the way.

The land of the Chalk is, apparently, quite reminiscent of Pratchett’s native Buckinghamshire, where he grew up. He paints a beautiful portrait of a land that is well-known and loved by its inhabitants, though possibly not properly understood by them. I did not grow up in Buckinghamshire myself, but I recognised it as a place you could class as home because Tiffany and her family have a lot of the same reactions to it that I have to the area that I grew up in whenever I manage to get back there. It doesn’t matter where you’re from: the Chalk is a place that Pratchett portrays as being home for his characters.

It’s a portrayal that is remarkably different to many of the other settings in the series. Ankh-Morpork, where the action of many of the other novels takes place, does not engender the same love and confidence in its inhabitants as the Chalk does (except possibly Rincewind’s feelings of nostalgia towards it in The Light Fantastic). Lancre, the other major setting of the novels, is portrayed as a sort of tiny kingdom that is taken for granted and endured by its inhabitants, rather than loved, although you get the sense in Wyrd Sisters that the locality is charged with the same sort of magical feeling that Tiffany sometimes taps into with her own home.

Something else that the Chalk reminds me of is the pastoral locations of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex novels. Hardy interspersed towns, villages and landmarks of his own invention amongst the real places in South-West England in his novels, making it an almost fantastical place itself, but it served to highlight the scenes and themes that he was writing in his books. Pratchett does something similar here when he talks about how the Chalk feels strangely unreal to Miss Tick, who’s used to more solidity in her landscape.

That solidity links us to another theme in the novel; that of finding your proper place in the world. Tiffany, as a younger (but not youngest) child in her family begins the novel by not really knowing where she belongs. She is intrigued by Rob Anybody and Miss Tick’s similar but different hints about her nascent magical talent, but she really isn’t sure of what she wants to do about it. By novel’s end she is making cheese, but we are also aware that this is not all she is destined for.

Part of what I love about this aspect of the novel – the learning to get by while you’re learning to do stuff that’s important – is something that is encapsulated neatly by Miss Tick (and abridged slightly by me to make it more pithy) early in the novel:

“If you trust in yourself. . .and believe in your dreams. . .and follow your star. . . you’ll still get beaten by people who spent their time working hard and learning things and weren’t so lazy.”

This pragmatism and lack of sentimentality towards being good at what you do is a vital lesson that most of us discover at some point and that some of us even follow when we learn it. The lesson provided in some other areas of media is pretty much the opposite; that if you have a magic feather or some other blanket against reality, it will guard you until you don’t need it anymore. The trouble being that we don’t always have that luxury of security and must rely on ourselves. And when we do learn to rely on ourselves, it would seem that we have obligations. As Granny Aching says in a flashback:

“Them as can do, has to do for them as can’t.”

As mission statements go, that pretty much sums up the Tiffany Aching books. She learns throughout the rest of the books the importance of service to others, a lesson that Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg, the other witches that we have spent the most time in this series with thus far, live by. The witches all believe that society is dependent upon people helping each other out. This credo of her grandmother’s influences Tiffany’s own thinking, as well.

Speaking of influences, there are a whole shedload of them in this book as well.

The obvious one is Labyrinth, the 1986 movie starring David Bowie as the Goblin King who kidnaps a baby boy because his selfish big sister Sarah (Jennifer Connolly) doesn’t want to babysit him. Tiffany’s time in Fairyland is largely spent avoiding the Elven Queen and working out a way to escape her mind tricks that would keep her a prisoner there. There are several scenes that remind the reader of Labyrinth – most notably a scene set in a ballroom near the climax. But the novel merely highlights how Labyrinth was also influenced by Lewis Carroll’s Alice books as well.

But stories set in Fairyland, or the homeland of the elves are rooted more firmly in mythology. Roland, the Baron’s son has been a prisoner there for a year but looks no older than he did when he was kidnapped. That idea of a night in fairyland equalling years or longer in the real world is one that has been explored more fully in other books and stories so I shan’t dwell on it further.

Because I really want to talk about the Feegles and their origins. They refer to themselves as Pictsies, which is a clever nod to the fairy folk of a similar name as well as the northern tribes of what became known as the United Kingdom in later years. What they do remind the reader of, though, is Smurfs.

Smurfs who have been cast as the Scottish rebels in Braveheart, perhaps, but who have come to that role through Trainspotting.

The Feegles are one of two links that get here with the other Discworld novels. The other link being Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg who turn up here in a couple of extended cameos to offer Tiffany some wisdom and encouragement (and to remind new readers that there are other books). Their appearance here is akin to the appearance of Vimes and Gaspode in The Truth: we see the established characters slightly differently because we are meeting them through the perspective of a new character. And since this new character is only nine years old and has to deal with all sorts of adventures that a normal child couldn’t be expected to deal with, she does need some encouragement from her elders who, for some mysterious reason, can’t help out on the adventure themselves. But since Tiffany is wise beyond her years and possesses the superpower known as “Not-Putting-Up-With-Any-Of-Your-Shit”, she solves her problems with very little cost to herself save a slight hardening of her conviction, the loss of some illusions and the learning of some compassion, which are good lessons for anyone to learn.

However, this may lead you to think that I didn’t enjoy it.

I did.

It suffers from the same things that made Maurice a mildly unsettling Discworld experience – the slightly less arch and carefree tone that characterises a lot of the other novels, the use of chapters, the smaller amount of footnotes, and the general sense of over-explaining some points to ensure that younger readers got the message.

But these are problems with adults reading literature for kids, not with this novel, to be honest. Pratchett doesn’t talk down to his readers, which is important, and like he did in Maurice, he makes only a few slight changes to his authorial voice, changes that will gradually disappear across the series as the audience for this book begins to grow older and start to read it as part of a series.

But, like Maurice, I didn’t really enjoy it upon first reading. It did read like a kid’s book to me, and I read enough of them for my day job, honestly. I don’t dislike children’s literature, but my version of escapism is written for me. And, if I’m honest, his earlier books for children the wonderful Truckers and Johnny Maxwell trilogies, really didn’t feel all that different to his grown-up novels, so why should this one be different?

The difference was that Pratchett was writing from a position of being the bestselling novelist in the UK when he wrote The Wee Free Men, although he was soon to be ousted from that spot. He’d also just written The Amazing Maurice, which had won the Carnegie Medal, so I really – when I’d had time to think about – didn’t mind that he was being careful with this particular storytelling venture.

I just felt that there was a certain air of caution in the writing, that it wasn’t being as chaotic and freewheeling as the other books, despite the presence of those agents of chaos, the Feegles. It felt like another book written by a bestselling author as award-bait: the fact that this was a novel set on a the Disc but the Disc itself was barely mentioned seemed like a bit of a cheat to me on the first reading, despite the fact that the setting was becoming less of a feature in all the books over the last dozen or so – despite being a major plot point in The Last Hero.

That changed on a second reading. By that point, I really didn’t care: this was just another book in my favourite series and Pratchett was stretching himself as a writer. And I don’t think it hurt that this novel was published in 2003, the Twentieth Anniversary of Discworld, with a lot of the attendant publicity that such a tome would have merited.

But it really is an excellent book, just different from everything else in the series… rather like Equal Rites had been different to everything else before it… or Guards! Guards! had been different… or…

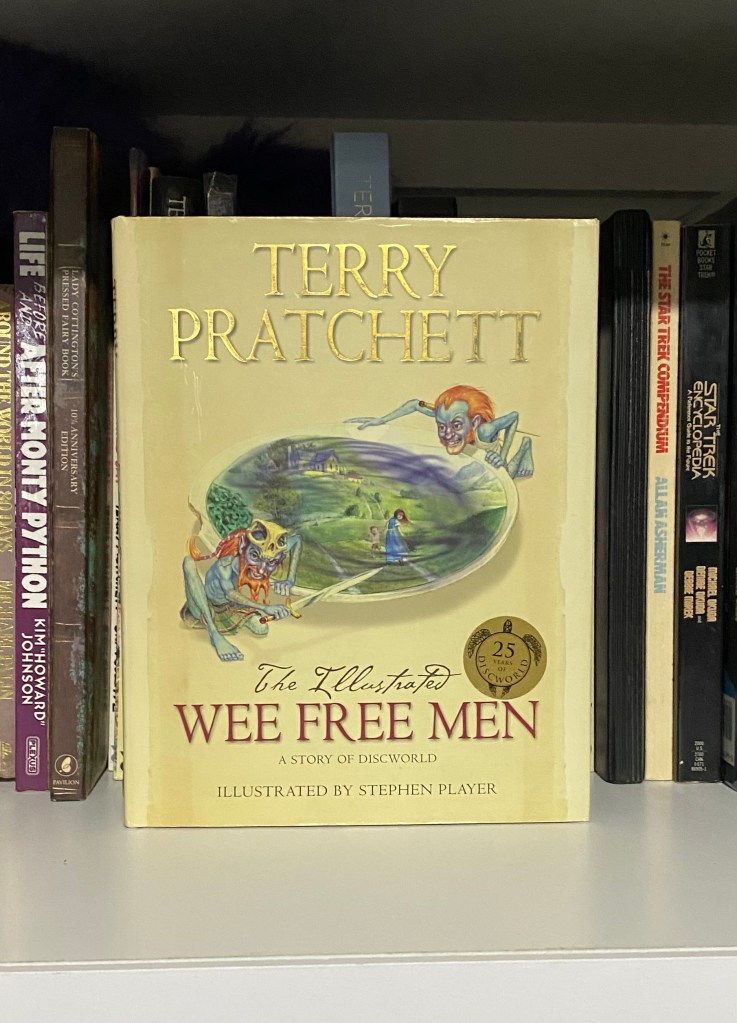

It was still the Disc. Pratchett was changing as a writer, just as I was changing as a reader. Frankly, I probably would have complained more if we had just gotten the same old stories book after book after book (I probably wouldn’t also have bought the beautiful 25th Anniversary Of Discworld edition which graces this post, either, if I hadn’t come around to it in some way).

So while Pratchett was growing as an author, we got to watch one of his creations grow as well, within a larger setting that was starting to settle down into being a beloved institution.

Coming Up Next: Polly just wants to find out what has happened to her brother, but she’s become a de facto leader of her group of soldiers… what will happen when they find out that she isn’t one of them in Monstrous Regiment?

4 thoughts on “The Great Discworld Retrospective No. 30: The Wee Free Men”