The Fourth Doctor (Tom Baker) and his two companions, Leela (Louise Jameson) and K9 (voiced by John Leeson), have arrived at the edge of the known universe. Escaping from the gravitational pull of a spiral nebula they seek solace aboard a nearby spacecraft. This craft, a remnant of the destroyed planet of Minyos, is searching out the P7E, its sister ship, which bears the precious race bank – a genetic memory of the lost planet, which could be vital for its survivors. The trouble is, the last time the Doctor’s people clashed with the Minyans, it was disastrous for both sides…

Underworld is the fifth story of the fifteenth season of what has become known as Classic Doctor Who. For those who are unfamiliar with the show, it was a BBC production that ran for 26 seasons from 1963 to 1989. It followed the adventures of an alien Time Lord from the planet Gallifrey. Possessed of a time machine known as the TARDIS, the Doctor spent his days having adventures with his friends, mostly humans from twentieth-century Earth, across the universe. There were seven incarnations of the Doctor in the Classic era, the most famous being Tom Baker, although he did have one of the lowest profiles as an actor before his tenure in the TARDIS began.

After its cancellation/hiatus/break in 1989 it was absent from the screen until a false start in 1996 where Paul McGann played the Eighth Doctor in a telemovie that can be best described as “uneven.” It was revived again in 2005, with Christopher Ecclestone playing the Ninth Doctor. It is still on the air: Ncuti Gatwa currently plays the Fifteenth Doctor (well he did until TEN HOURS after this post went live).

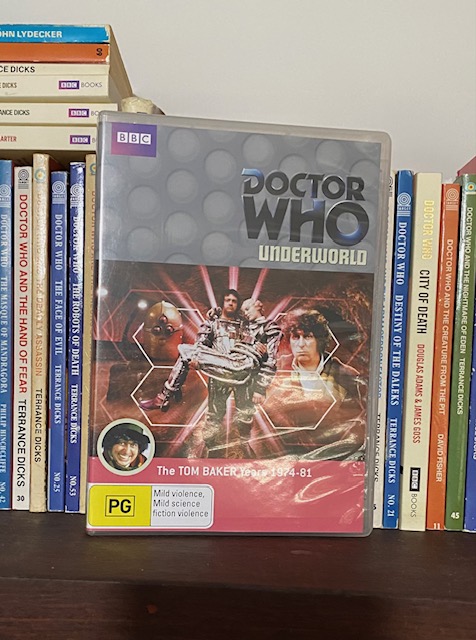

Anyway, Underworld aired across four episodes in January 1978. It is almost universally panned among fans of the show for its slow-paced storyline, ordinary (as opposed to “special”) effects and for a reasonably imaginative but poorly produced script.

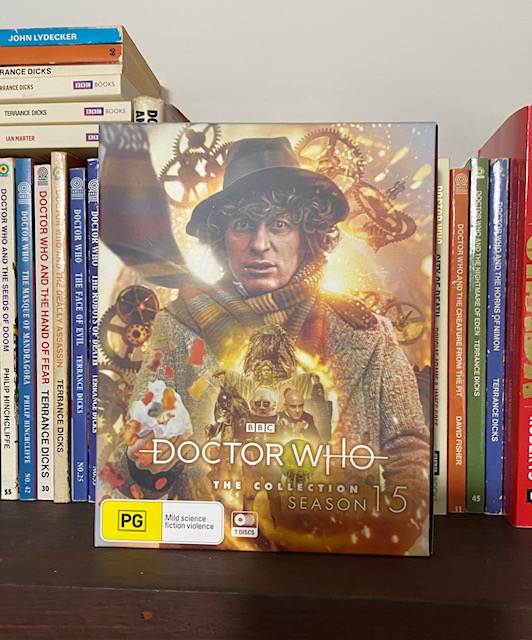

Season Fifteen should have been a triumphant year for the show. Graham Williams was taking over as producer after an acclaimed three seasons by his predecessor, Philip Hinchcliffe; Tom Baker had become a household name; and Louise Jameson had just come on board as a co-star and was proving herself to be one of the best actors ever cast in the show’s history in any role.

Everything was poised for this success to continue.

Unfortunately, there were several factors that contributed to it not happening.

Don’t get me wrong: Doctor Who continued to rate strongly and remain well-thought of in the industry, but a downhill slide that some fans maintain continued until the Classic era’s axing/resting in 1989, can be possibly pinpointed as beginning in this season.

The first of these is the budget. When Philip Hinchcliffe was “let go” as producer – he was moved on to a high-profile prestige drama after complaints that some stories he produced were too violent – he instructed his subordinates to pull out all the stops on the last two stories of his final season, Robots Of Death and The Talons Of Weng-Chiang. These are two fondly remembered stories (although some racist elements in Talons have tarnished its memory in recent years), but the budget for them went quite a way over their allotted portion. So the powers-that-be decided to snip some budget from the following season’s allowance. This might have been merely difficult to manage in a regular year, but 1977 was also a year famous in the UK for its galloping inflation. Between the start of the production of Season 15 and the conclusion of it, the rate of inflation meant that there wasn’t enough money to do justice to the last two stories of the season (Underworld and The Invasion Of Time).

There was also the issue that script editor Robert Holmes had only agreed to stay on for half the season and was training up his successor, Anthony Read, during this time as well. Meanwhile, the planned first story of the season, a vampire story by veteran Who writer Terrance Dicks (more on him shortly) had fallen through because of a high-profile adaptation of Dracula that the BBC was planning. Dicks hastily penned a replacement story to run in its place (The Horror Of Fang Rock, which is superb, by the way – the Dracula adaptation… less so).

To further confound matters, Williams was under instruction to tone down the horror aspects of the show that had gotten Hinchcliffe in trouble. He also had to deal with the demands of Tom Baker who was under the firm conviction that the show couldn’t survive without him, and was behaving accordingly.

So when the time came to record Underworld, things were looking grim.

For some context, let’s look at the story, by seasoned writers Bob Baker and Dave Martin (Bob Baker is possibly more famous for his collaboration with Nick Park on the Wallace And Gromit films). They were experienced at writing Doctor Who having penned several stories together for the show before, most famously, the tenth anniversary story, The Three Doctors.

The Doctor explains to Leela that his race, the Time Lords, discovered Minyos quite early in their explorations of the universe. They gifted the Minyans with technology (including the secret of bodily regeneration) and were treated as gods in return. But the Minyans rose up and overthrew their Time Lord rulers, which led to their policy of non-interference, a law that the Doctor has run afoul of many times, since his remit is to travel across the universe and… well, interfere.

Not long after their arrival, the Doctor and the Minyans locate a signal from the P7E. However, it is coming from inside a newly formed planet. When they crash land into it, they discover a rigid society of oppressed humans known as Trogs, ruled over by the Oracle (the P7E’s resident AI). The Minyan crew, led by Jackson and comprising Orfe, Herrick and Tala, realise that their quest of 100 000 years is over and vow to retrieve the race banks and head home…

The script was set largely on a spaceship and in a network of caves below the surface of the planet that has formed around the P7E. Unfortunately, there was only enough money to build the spaceship set. Cunningly, the spaceship the Doctor, Leela and K9 land on is the sister ship of the P7E, so some money was saved by redressing it for scenes set on them both.

But the caves were another matter. The problem was solved by constructing a model of the proposed set and projecting the actors onto shots of it through a process known as Colour Separation Overlay (CSO), an early precursor to the Green Screen beloved of filmmakers these days.

Because it was the 1970s, it was not entirely successful. But on the television sets of the day, it was also less noticeable (something also hard to spot on the television sets of the day are some cheap and nasty details, like the clips being used to connect K9 to the R1C’s computer being undisguised bulldog clips). But what was noticeable was that the thin story, already stretched out to four episodes, just made any flaws in the production stand out even more.

Performances in this story are mixed: Baker and Jameson are excellent, as usual. Jameson has always been the highlight of the season for me: Leela was a warrior from the Sevateem tribe, a lost expedition stranded on a jungle planet, until she joined forces with the Doctor. Her policy of knifing enemies first and not bothering to ask questions at all was a refreshing change from the previous companions who were brave but had a tendency to scream at the slightest hint of peril (When the show began it was more of an ensemble piece, but the characters soon devolved into a team led by the Doctor with his companions frequently relegated to monster bait and expositional straight men (and women) in order to further the plot).

Leela’s mix of ferocity and naivety worked amazingly well. At this point in the season she was beginning to tone down her violence somewhat in favour of finding things out, but it was never far from the surface.

Tom Baker’s portrayal of the Doctor was another matter. He had followed the performance of his immediate predecessor by possessing the same acid wit and idiosyncratic dress sense, but he was unpredictable and presented himself as a more wide-eyed and innocent wanderer of space and time, with a companion to keep him grounded and focused on getting things done.

When these two were joined by K9, a robot dog, earlier in the season, they created an absolutely magical team for me. The chemistry between the three was palpable, even if the two human members of it never really did get along all that well in real life.

They are joined in this story by James Maxwell, Alan Lake, Jonathan Newth and Imogen Bickford-Smith as Jackson, Herrick, Orfe and Tala, of the R1C (which is never named in the script). In the caves surrounding the P7E, they are joined by Norman Tipton as Idas, and Christine Pollon as the voice of the Oracle, the P7E’s computer system.

The space travellers spend the first episode playing their characters as tired and exhausted after their long quest, but once they arrive on the planet, this exhaustion merely looks wooden. James Maxwell convincingly portrays a man who has lost sight of his own existence in the service of an increasingly meaningless quest; Newth and Bickford-Smith barely have any lines beyond Episode 2; while Lake gives an astonishingly energetic performance across all episodes, which only serves to throw everybody else’s acting into sharp relief.

These characters are thinly-disguised avatars of characters from Greek mythology. This is signposted by the Doctor calling Jackson “Jason” in the last minutes of the story, explaining to Leela that:

“… perhaps those old legends aren’t so much stories from the past as prophecies of the future…”

Jason, of course, refers to the Captain of the Argo, who searched for the Golden Fleece of Greek legend. You can look at his crew – Orfe as Orpheus, Herrick as Heracles – to find further clues, but it falls apart a little when you examine it more closely. Tala, for example, is modelled on Atalanta, a famous huntress of legend… but she didn’t sail with Jason. Likewise, the P7E represents Persephone, a woman who spends half of each year in the Underworld, causing our seasons. Also not associated with Jason and his Argonauts. The Minyans themselves were said to be the first invaders of Greece. There are other characters and names that suggest a mish-mash of myth and legend, but while the basic idea is sound, the execution is a little off.

The entirety of the story just feels a little off, too. Baker and Martin’s script runs under length so there are all sorts of short cuts to pad out each episode to an acceptable length. There are shots that are repeated to fill in time; recaps of previous episodes that are far longer than in other stories; there’s a lot of unnecessary exposition and padding which doesn’t help with the incongruities of the story – for example, the Doctor has K9 produce a map of the cave system which Idas, an inhabitant of it, calls “The Tree Of Life” despite having lived in a cave all his life with no sign of any kind of plant life let alone a tree.

So why have I written 1800 words about it so far, then?

Well, it’s largely because of the novelisation.

See, during the first few years of Doctor Who’s existence, in the 1960s, there were three books written that adapted some early stories. During the 1970s, Target Books, a children’s imprint of W. H. Allen (sadly defunct now), negotiated for the right to publish more novels based on the adventures of the Doctor. These were amazingly successful, selling over 8 million copies by the early 1990s, mostly because until the advent of home video, they were the only reminder of many stories, some of which had been famously destroyed by the BBC. They were written by a wide variety of authors. The preference was that the story’s scriptwriter would pen the novel but they had frequently moved on, died, were engaged in other projects or didn’t have the time for it. So the job would be handed on to an in-house author. By the late 1970s, this was usually Terrance Dicks (1935 – 2019).

Dicks was ridiculously qualified to write for Doctor Who: he had worked on the program for several years as a script editor, contributing much to the lore of the show, so he was a natural fit for writing the novels. He was also a prolific novelist outside of television as well, producing a wide range of titles in different genres. Of the nearly-160 adventures of the Doctor in the Target range, he novelised nearly 70 of them. His writing was easy to read. He had a compact style that relied on simple descriptions and imagery to get the message across. But he also had a flair for the dramatic and captured the imagination of the reader. Like many writers of a long-running series he relied heavily upon repetitive images and phrases across his many books, but he always delivered a decent reminder of what had been seen on-screen, which was what most readers were after from his work. Even his less-polished efforts (mostly from about the late 70s- early 80s) are decent reads and – because of the required page length of the series at the time (between 100 – 140 pages) – are quite easy to read in a single sitting.

Dicks had written 5 Who books in 1979 and he produced 8 more after Underworld in 1980. Fortunately he slowed down after this, producing just four or five a year until 1990 when the series was more or less complete. He did write several more non-televised stories after that, but we aren’t here to discuss them today, alas… or fortunately, depending on how you feel about The Eight Doctors.

Underworld starts with a prologue. This sets out the history of the Minyans and explains their conflict with the Time Lords and why they are out exploring the edges of the universe at the start of the story. It’s compact but spans thousands of years of a conflict between a race of mortals and their rulers that they consider to be gods. It starts with the phrase,

Once there were the Minyans.

To someone with even a whiff of imagination, that immediately sends them into the realm of myth and legend, with its hints of ancient times and lost races.

Dicks often gave out some backstory to his novels. I’m currently at the twentieth season of Doctor Who in a reread of the entire series and I’ve had an opportunity to study how Dicks retells a story. Frequently, if the story is pretty solid (his retellings of his own scripts spring to mind), you could slice the book into equal parts (one part for each episode) and find that they are roughly the same length. For some of the weaker stories he might spend more time fleshing out the story in the earlier part of the book so that the rest of the story flows better and makes more sense. For some stories that did not work terribly well on the screen he might also include a prologue to explain some backstory to what the Doctor is about to experience.

Underworld features a prologue. It has a page count of 117 pages (123 less the title, copyright and content pages). Of those 117 pages, 38 are taken up with getting us to the end of Episode 1. That’s about a third of the book.

I bloody love it, to be honest.

I love it more than the televised story, to be perfectly honest.

And if I’m completely honest, I can trace me becoming a proper lifelong fan of Doctor Who back to this book.

I mean, I had several of the novels in the series prior to this, and I adored the show already. But Underworld captured my imagination in a way that no other story had.

For one thing, I was 10 years old when I first read it, and I was just beginning to branch out from books in my house and local library to books that I was discovering on my own. It took a couple more years before I started to actively seek out authors and books that I enjoyed but the Doctor Who books showed me that there was a wider world of literature out there. Terrance Dicks was a big part of that: he made allusions to other writers or works of art throughout his novelisations, giving me scope for a ridiculous amount of “a-ha!” moments later in life. He explained the motivations of characters clearly, making performances that may have lacked clarity and conviction on the screen much more interesting and nuanced on the page (and on the screen when I rewatched them). And he created, in his characterisation of the Doctor, someone who was vulnerable but reliable, flawed but honourable.

And he helped build a mythos and a wider universe that the Doctor travelled in.

The prologue to Underworld is a perfect example of that. It takes a couple of lines of dialogue from the story and creates an entire history from it. We get the proper backstory for Herrick’s rage at finding a Time Lord aboard his ship; a real explanation of the exhaustion and ennui that the crew are facing, as well as a proper sense of the obligation that the Doctor feels for helping these travellers to solve their problem.

The Doctor and Leela and K9 become – in this story at least – part of a much bigger world. The story ends with Jackson and his crew going home, with hints that their quest might be over but that their adventures are continuing. They leave the crew with renewed hope. You get the sense that this crew are going to continue their story in a way that other stories don’t – there’s a lot of adventures in Doctor Who that end with a tyrant overthrown, or a monster vanquished or peace achieved and, while I adore the lot of them, you often feel that the story is over for those guest characters. But you just know that the crew of the R1C are going on to have more adventures on their journey home… and you get the sense that they aren’t going to end when they arrive there, either.

Dicks takes an adequate script from a flawed production and gives it a weight and heft that it possibly doesn’t deserve to have.

Of course, a lot of this is just me reading my own enthusiasm for the show into the pages of its books. But largely because of Underworld, the stories of Season 15 are my favourite complete season of the show (coincidentally, the entirety of the season was also novelised by Dicks alone, the only instance of this in all 26 seasons). This adventure and the novelisation of it, came into my life at exactly the right moment to make me a complete fan.

But while I love the story, I am not blind to its faults. It is not a good piece of television, although there are some virtues to be seen in it: Episode 1 is great fun, while the terrible special effects in the remainder of the story only heighten the flaws of the rest of the story.

Like anything in life, it’s what you get out of it that’s important. And that’s only enhanced by what you put into it. For me, it’s the suggested history that the prologue gives out explaining why the Time Lords became what they were like later” added lore that (retroactively) adds lustre to background details of the show’s history. And that detail is thrown into sharp relief by the events of the following story, The Invasion Of Time, which features the Doctor seemingly aiding then thwarting an invasion of his home world. That, too, is a production plagued by problems, but it still manages to be entertaining and exciting in a lot of places.

But The Invasion Of Time becomes deeper and more significant because it is illuminated by the events of its history, still fresh in the viewer’s mind from the events of Underworld. Which, for all the faults of both stories, is proper storytelling magic.

You can find out more about Doctor Who at https://www.doctorwho.tv/