In 1949, Helene Hanff (1916 – 1997) began a correspondence with a bookstore in London. The New York-based writer wanted a connection with the English literature she had grown up loving and buying books from the source seemed to be the easiest option. The next twenty years were filled with business letters that became less formal as both sides of the correspondence – Hanff and “FPD” became acquaintances and then friends, despite never meeting each other.

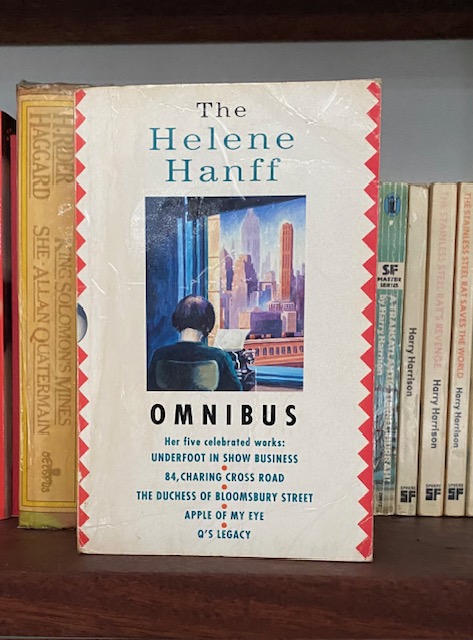

I’ve covered one of Helene Hanff’s other books elsewhere on this blog. However, 84, Charing Cross Road (1970) is where I became a fan of hers.

First things first: for a collection of letters, it is surprisingly readable. When I first read it in the mid-1980s, I hadn’t yet read Dracula, Pamela, or Les Liaisons Dangeureuses (and the middle third of my own debut novel was yet to be conceived as well), so my knowledge of a book comprised entirely of letters – epistolatry is the fancy name for this genre – was almost completely new to me (I had read Stephen King’s Carrie a couple of years previously, so the flavour was not unknown to me).

I was initially put off by the compact size of the book – just under a hundred pages in most editions – but I discovered that the quality of the text more than makes up for the quantity. What drew me in was not just the snappy writing on Hanff’s side of the correspondence, but the easy familiarity with literature that nearly all sides of the correspondence had. At the time I was just beginning to branch out beyond the books I knew into a wider world of literature that I was vaguely aware of through quotes and references but had only a nodding knowledge of.

So naturally, a book that casually drops mentions of Shakespearean characters into a discussion of soccer with a measure of respect but not necessarily veneration was a balm to my soul.

Let’s take a closer look at it.

It begins innocuously enough, with Hanff writing to the bookseller Marks & Co in October 1949, requesting some titles. It’s written politely but in a style we might call “casual formality.” She hears back from them twenty days later with a list of the titles they have available.

They mention Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt. At the time of reading I had no idea who they were. However, I would encounter Hazlitt in David Lodge’s Small World a couple of years later, and begin a slightly more than nodding acquaintance with Leigh Hunt not long after that.

This letter, written by “FPD” (Frank Doel, as we would soon learn) begins with the casual British addressing of Hanff as

Dear Madam

Being Australian (and quite young in more than years) I thought nothing of it. However the third letter in the book, in which Helene praises the quality of the books as well as bemoaning her inability to “translate” dollars to pounds, ends with the postscripted query

I hope ‘madam’ doesn’t mean over there what it does over here.

The next letter is simply addressed

Dear Miss Hanff

Following this, the tone becomes increasingly casual and conversational, with Frank still maintaining a veneer of professionalism but showing his warmth and humour through his writing.

Eventually, Helene becomes a regular customer of Marks & Co, sending food parcels to Frank and the rest of the staff who are suffering under the rationing that was the norm in Britain for those immediate post-war years. Her generosity makes her a beloved friend as well as client and we learn the stories of many people who work with Frank, as well as that of his family also.

She also repeatedly plans to visit the bookshop but is always scuppered by reality getting in the way: her teeth need work, cancelling one trip before it was properly planned, while moving apartments takes care of another. Helene’s literary career, while occasionally successful, is filled with the mundanity that plagues us mere mortals.

And then, following a letter in which Frank is talking about his children and his hopes for their future, there is a note from the firm’s secretary informing Helene that Frank has died following a routine surgery.

The book closes out with a letter from one of Frank’s daughters, giving permission for Helene to publish the correspondence in book form, ensuring that their friendship lives on.

The appeal of 84, Charing Cross Road to someone who was a reader of primarily genre work is puzzling at first. But it’s a book about people who love books and who care about the folks around them. I’ve spoken elsewhere on this blog that, while I wasn’t ostracised for my reading, it was regarded amongst a lot of my friends as how they characterised me. And while I had several friends that I would discuss books with, I frequently felt that I was screaming into the void a little bit when talking about the books I read; either because they were too trashy and pulpy for general consumption or too niche and obscure (which is the same thing but with patches on the elbows) or even too commonplace for general consumption. 84 spoke to me about books as a common language, as touchstones to a shared understanding of life. And when I came to a lot of the books mentioned throughout its pages later on in life, I felt a lot less intimidated by what they were.

But it’s also a book about dreams: Helene, who had never achieved the success she had dreamed of and worked for in her earlier memoir, Underfoot In Show Business (1961), finally achieved it with this book. In fact, there’s a moment in that book where she talks about “Flanagan’s Law,” an axiom devised by a producer friend of hers which goes

No matter what happens to you, it’s unexpected.

The copy I had access to belonged to my parents. Because I was getting to an age where I was starting to loan out my own books and not get them back and I didn’t want to do that to anyone else – I decided I needed my own copy. My solution was simple: once I started university, I had access to the photocopier in the library and it was possible to copy articles for class reading and research. Every time I needed to get something copied for a class, I would copy a few pages of 84. This was a lengthy process – and a terrible breach of copyright – but, like Helene with the books she bought, I desperately wanted my own copy of this treasure. (If it helps, I’ve paid proper money for a couple of other copies of it over the years as well)

I read it almost obsessively for several years. And, while I didn’t treat it like a scavenger hunt or checklist, I was always pleased when I discovered a book referenced within its pages during my own reading. I began to hold my own more confidently in discussions about literature and books largely because of Helene’s own enthusiastic attitude to her own reading. In fact, this scattergun approach to reading that I developed across my teens and into my twenties and thirties may well have come about because of 84.

I know that when I read about how she had begun her exhaustive reading I felt a shock of recognition, realising that her approach had been adopted completely independently and unknowingly by me: she talks across several of her books about how, when she came to a footnote in a history of literature (usually by sir Arthur Quiller-Crouch, known widely as Q), she would hurry off and read the text being referred to by the footnote, then come back and continue reading until she came to another footnote, whereupon she would hurry off and do more backreading. It was an approach that I had adopted, albeit in a far more slovenly and lazy way – but I do always read footnotes, partly because there’s a lot of interesting information to be gathered from them for further research, but mostly because Sir Terry Pratchett made them so appealing to readers of his books.

In her follow-up book, The Duchess Of Bloomsbury Street (1973), Helene expounds upon the success of 84 and all the wonderful things that she was able to achieve at a time of life when she thought that any kind of success was behind her. In Q’s Legacy (1985), one of her last books, she reflects more deeply on what the success meant and how it changed her life:

What fortune teller would ever have had the nerve to predict that the best years of my life would turn out to be my old age?

It’s an encouraging sign as we approach the end of middle age and what we think of as the final fading of the promises of our youth to know that things aren’t necessarily beginning to end for us.

You can find out more about Helene Hanff at http://www.helenehanff.com/