In 1989, Kenneth Branagh was on the cusp of greatness. An acclaimed stage actor, he had just released his filmed version of Shakespeare’s Henry V onto a public that adored it, hailing him as the greatest Shakespearean actor since Olivier (which may have been premature since Olivier was still alive at this point. How did he achieve all of this before he turned 30? In order to answer this question, but mostly to finance his fledgling production company, Branagh penned his autobiography, titling it Beginning…

Today, Sir Kenneth Branagh is not a titan of the stage and screen, as prophesied by some critics; however he has had a career that is successful by any standard you might want to measure, crossing easily between genres and media as if there was no difference between them.

I’m going to go a little backwards here to the normal format of these posts, because this book needs to be placed into some kind of context before we take a look at it.

Usually, we look at what the topic is about, then go into some kind of detail about where it came from before discussing why I like it.

To me, this book seemed to come from nowhere, but it’s filled with people and information that I had been aware of for quite a big chunk of my life – so the distillation of what was in it is what is important here, not necessarily the book itself.

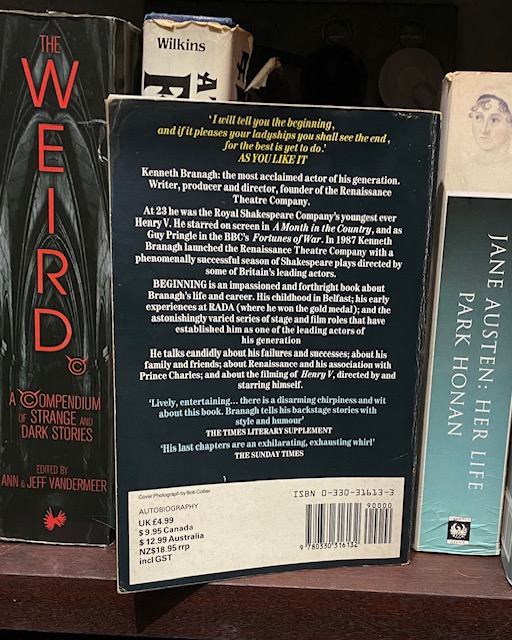

I first read Beginning in 1990, the year after it was published. It was the paperback edition, of course.

Branagh had exploded into the showbiz world, it seemed, overnight (I have learned since then that people frequently spend years laying down enough groundwork, reputation and grit so that they can become an overnight success).

But Branagh’s rise was far more obvious to our friends in the UK than it was to us in the Antipodes.

He’d acted over here in an adaptation of D. H. Lawrence’s novel The Boy In The Bush – which he detailed entertainingly in Beginning – but aside from that he was an unknown quantity to me before I heard about his film of Henry V.

But I went and saw it, not entirely sure of what to expect from it. I kind of felt obliged to, having just begun a bit of a thing for Shakespeare, ignited by a fairly intensive study of some of his plays at university, followed very quickly by a production of Romeo And Juliet where I essayed a decent amateur performance of Mercutio (our local critic didn’t quite accuse me of milking the part for all it was worth but he came close). But all this followed a reading of Richard III in Year 12 and the purchase of Laurence Olivier’s memoir On Acting a year later, which was a fun retread of his Shakespearean greatest hits and some of the work that he put into them. One of our local television stations had even screened Sir Laurence’s Henry V in the lead-up to Branagh’s version being released in Australia (several months after the rest of the world had seen it, I might add).

I saw it, and I loved it. It’s not a perfect film, but it is very good, and he manages to not only turn in an excellent performance, but also direct a creditable film debut that looks a lot more expensive than it really is.

So I was more than ready to soak up his autobiography.

According to a lot of reviews that I’ve read, there was a fair amount of disdain thrown at Branagh for writing it: he was at the start of his career, some said; others said he was only writing it to finance future productions he wanted to present. Still others sneered at the “luvvy” attitude he took towards his fellow actors.

Branagh admits to the first two of these issues in the introduction: he had received several offers to write books, so why shouldn’t he have done it? The interest was there after all – and if he hadn’t done it, somebody else would have written it and made some money for themselves.

He further qualifies these concerns with

It’s the story of a particular talent, and how that talent was combined with a measure of ambition and some quite extraordinary professional good fortune. Above all, it describes a first stage, from which it seems too early to draw far-reaching conclusions.

This is simply what happened to me.

Branagh is an excellent storyteller: he is also honest enough to admit when he is in the wrong and when he has pushed too far. By this point in my life I had read an awful lot of showbiz bios (or should that be “a lot of awful showbiz bios”…?) and was becoming aware of what an experienced actor with enough chutzpah can get away with if they brazen things out. Branagh was quite the refreshing change – although he might also have just been showing some humility at the start of his career to not burn any potential bridges that he might need in the future.

At any rate, I lapped up this book.

He spoke a lot about how he went through Drama school, as well the experiences that led up to him deciding to become an actor. I loved reading about his experiences of discovering connections between actors and their roles through his obsessive retention of information about films seen at the cinema or on television as a youth:

It was around this time that I saw Burt Lancaster in the film The Birdman Of Alcatraz. It is a gripping story about a convicted murderer who finds peace rearing birds in his prison cell. I was struck by how real it seemed. No one appeared to be “acting.” Lancaster’s own performance was tremendously powerful and affecting, and I was so engrossed that I studied the end-credits list so that I could check the names of the other actors and everyone else responsible for the movie.

That obsessiveness struck me with a hammer-blow because I was exactly the same not only with actors and shows I followed, but also with authors I loved: I would hardly ever knock back the chance to read a book or story that an author had recommended in an interview or had placed a blurb on the cover of another book for.

I also loved his self-deprecating honesty: when he talked about his success at doing sport in high school…

I eventually became captain of the rugby and football teams, more, I suspect for my innate sense of drama – I loved shouting theatrically butch encouragements to ‘my lads’ – than for any real sporting skill.

…I felt a real kinship with him – not because I was good at sport but because I had an occasionally quiet and serious nature that people took for maturity which meant that I sometimes wound up disappointing people who had taken me for someone with more depth and skill than I actually had.

But it was when he wrote about his auditions for drama school, and the work he put into preparing for a role that I really took to him: I mentioned earlier that I had read an awful lot of actor bios by this point… well, loads of them talked about what their subjects did to prepare for a role, but this was the first one where it felt real, where we were given a proper insight into what the actor was thinking and the way they would put their heart and sole into the part. I mean, I knew from On Acting that Olivier always started his character work with the nose but I didn’t know much else about his process. He had some pithy advice about “loving the character” as well but that didn’t really get to the heart of what he did to act – I suspect now that his process was largely internal and developed over the weeks and months of rehearsal, and that’s tricky to put down in bullet points for someone trying to crack the code. But apart from one role, he never spoke much about how he would create a part beyond the superficial (although his description of Iago as an ambitious officer stunted in his career while less qualified men are promoted above him is wonderful)

Branagh goes into a fair amount of detail about what he does to create a role. He talks in some detail about a lot of his parts, but it’s when he lands the role of Henry V that he lets you know more about his process: his detailing of what he went through to understand the part and then the eventual visit to consult with (then) Prince Charles about what it is like to grow up in the public eye and how that influences the way you interact with other people.

For me, still believing that I was doing a decent job as an amateur actor and wanting to learn as much as I could about it, this was gold.

And, of course, the book concludes with a lengthy section that is the diary of filming Henry V. Looked at in one way, you can see this as the culmination of Branagh’s young life: he takes all the great heroes, mentors and friends he has collected in the few years of his career – Judi Dench, Brian Blessed, John Sessions, Derek Jacobi, Emma Thompson (you were a bloody fool, Ken, letting her go) – and gets to create something cinematically magical around them. And, honestly, it’s as good a place to break off a story about the start of a career as any.

Of course, his career since then has not lived up to that early burst of energy and promise. But honestly, who’s could?

Branagh followed up the success of Henry V with the reincarnation thriller Dead Again. I saw it as soon as I could and loved it: I’d read an interview in which he had been offered any number of historical/Shakespearean films in the wake of Henry V and had decided to do something completely different to it as a way of stretching himself and not getting pigeonholed.

It is a good film. It has some problems: Branagh’s roaming American accent and the rather ludicrous death of the villain of the piece drag it down but the rest of it is fine. It’s noirish in flavour and treats the audience respectfully and intelligently. He followed that up with the Big Chill-ish Peter’s Friends and then returned to Shakespeare with Much Ado About Nothing, which is possibly his most-loved film. His career has never really hit the doldrums since then but he has never scaled the dizzy heights he experienced in that brief time after Henry V.

Which is fine: he’s directed some films that have never been less than entertaining and he has essayed some performances that are solid and thoughtful.

He also managed to fulfill a bit of a bucket list item for me as well.

I mentioned Olivier’s On Acting a while back: in that he talked about how John Osborne’s play The Entertainer had managed to rescue his career from a stint in the doldrums during the 1950s. I read a bio of Sir Laurence not long after in which he talked about it rejuvenated the way he approached a role and was, in fact, a breakout part for him in that he was playing the sort of character he could have become himself if his career had gone another way (it is the one part eh describes in any kind of real detail in On Acting).

A few months after that I read Arthur Miller’s bio/memoir Timebends: A Life and he talked about meeting Sir Laurence while his wife, Marilyn Monroe, was making The Prince And The Showgirl with him. and going to see John Osborne’s debut play Look Back In Anger (Branagh and Emma Thompson played the leads in a production of that, as well) and asking quite casually if he’d write a play for him. The result was The Entertainer, the story of has-been music hall star and impresario, Archie Rice. The story of the production, the milieu of the play, as well as the reception to it fascinated me and made it something that I really wanted to see (I knew enough about the limits of my own talent to not be bothered about acting in a production of it).

Branagh later played Rice in a production that was screened in a local cinema here in Perth in 2016, so naturally I went off to see that. And was not disappointed, although the play itself has themes and ideas that have been largely superseded (as an aside, Branagh also played Sir Laurence in My Week With Marilyn, a film about the movie being directed when he met Osborne).

But while I was thrilled to see an actor I admired in a part I had wanted to see for a long time, I was more thrilled to see an actor whose career I had followed for a long time still trying to push himself in roles that are physically and emotionally demanding (he was nearly ten years older than Olivier was when he played the part). A couple of years later, I saw him return somewhat to his roots in the Shakespearean biopic All is True, a moving but rather slow depiction of the Bard in his last years.

Which brings us back to Beginning. At the close of that book, Branagh talks about what his plans for the future are: he wants to continue mixing theatre, film and television, but taking care not to repeat the mistakes of administration and working conditions committed by other companies he has worked for and that he has also fallen into. He talks about the state of his career and his craft, as well as the lack of opportunities in his personal life to see work by other performers:

I have never given myself the chance to make any serious assessment of my work, and I have thus denied myself many chances to improve as an actor, which now stands as my primary concern.

This concern about the state of his career while he appeared to be at the top of the world, was quite grounding to younger me, and while I haven’t always kept on that line, it’s a direction that I’ve always tried to travel in, regardless of where my life has taken me. And that desire to improve at whatever craft I ply is something that is rarely far from the forefront of my thinking whenever I try something new in my life, or find myself feeling stale at something that has become commonplace.

Which is not a bad legacy for a book written largely for the money.

You can find out more about Sir Kenneth Branagh at https://www.branaghcompendium.com/