Aandred is the Master of the Hunt, servant to the all-seeing Droam, Lord of Neverland. Aandred and his dogs patrol the once-famous island and keep its shores safe from the incursions of “Bonepickers”, the humans who live on the other islands and are now searching to expand their world. But Aandred does not count on meeting a Picker and finding himself becoming sympathetic to her cause…

Ray Aldridge is a US author. He is famous for his Emancipator series (1991-92) but he is probably best-known for his short fiction. His short story (or “novelet” as the contents page of The Magazine Of Fantasy And Science Fiction refers to it as) “Steel Dogs” was a Locus Poll nominee for the year it was published (it lost to Orson Scott Card’s “Dogwalker”).

Let’s take a closer look at it.

Aandred waited in the egress lock, jammed in with the horse and the dogs. In that small place, the air was dense with the stinks of machine oil and ozone and hydraulic fluid.

From the beginning we are getting clues that this is something out of the ordinary: most of us have some knowledge of what horses and dogs smell like, and it isn’t like a workshop.

The next paragraph starts with

Aandred flipped open the panel set into his forearm, studied the telltales there.

We now know that Aandred is something more than human, and that the somewhat familiar setting of a hunter with his horse and dogs is slightly off from what we are used to.

Then we meet Droam, Aandred’s master:

“Ready, huntsman?” Aandred hated the sound of the castle’s voice in his head; it was an intrusion, a reminder that he was Droam’s property.

We’re only a couple of hundred words into the story but we know that Aandred may be more than human but less than autonomous. The setting is already hinting at being something futuristic but with traces of a more primitive, feudal past.

Aandred sets off to fulfill Droam’s mission for him: to kill a party of explorers from another island – giving us another clue about the setting – except for one, to be kept alive for questioning…

He does exactly this, bringing the survivor – a woman named Sundee Gareaux – back to the castle. Droam’s initial attempts at questioning her fail so Aandred is tasked with looking after her and healing her so that she can deal with an interrogation.

When Gareaux is sufficiently revived, she and Aandred swap stories: she is a member of an exploratory team from another branch of the colony that is looking to expand their borders: Droam’s island looked to be uninhabited so they believed that to be a suitable prospect. Aandred in turn tells of how the island was once a resort filled with artificial life catering to those with a bent towards the fantastic, hence his mediaeval appearance and calling, and the monstrous or ethereal miens of his colleagues:

“At first they intended to staff Droam with robots in the shape of the Ancient Folk of Old Earth: elves, trolls, fairies, dwarfs, wizards, and witches. But… (r)obots had one flaw – they were predictable.”

Aandred reveals that he and most of the other “staff” are, in fact, “revenant personalities”: the personalities of people uploaded into robot form, achieving some sort of immortality. And, because not everyone appreciates being imprisoned for ever in a suit of metal controlled by someone else, many of them were convicted criminals. Aandred reveals that he had been a once-feared pirate given the opportunity to live this half-life instead of facing execution. And he has done so for seven hundred years…

Eventually, Gareaux’s story and plight soften Aandred’s cynicism and inspire him to rebel against Droam. I won’t give away the rest but if you can find it, “Steel Dogs” is well worth your time.

It is atmospheric, evoking a decadent future world with some mere hints and glimpses, letting us know that things are markedly different to what we are familiar with, although humanity’s curiosity and need for new experiences appears to be unchanged despite being given much wider opportunities to sample from.

It’s a story that has a lot of the features of Cyberpunk; a decadent future filled with Haves ruling amorally or disinterestedly over the Have-nots; characters who are augmented with technology leading to some sort of loss of their individuality or autonomy; a slightly denser and more literary style than you might find in “mainstream” SF; and characters who live on the fringes of society, mirrored with their morality reflecting this dual existence they are forced to lead.

(I’m not really a fan of Cyberpunk: if I hadn’t already read a heap of New Wave stories and novels from the 1960s, doing much the same thing that Cyberpunk did in the 80s, but without the benefit of long, tedious descriptions of technology that was out of date before the story was published, I would probably have enjoyed it a lot more. People who had previously sneered at SF suddenly brandishing their copies of the Mirrorshades anthology at me while rhapsodising how “SF was an important literary movement now” didn’t help, either.)

Aandred himself is an interesting character: that he was once a villain should come as no surprise to the reader, given his ease at dispatching and not giving any further thought to Sundee’s companions. That he hasn’t sunk into mindless routine and violence like some of his colleagues is possibly a credit to him, but his naturally rebellious state may have contributed to that as well.

His journey from impassive huntsman to rebel is sparked by merely being in contact with Sundee and learning about what people have been up to outside of the resort. It reminds him of his past life and the importance of individuality amid the electronic white noise of his current existence:

”Droam calls me Huntsman. But I had another name when I was a man.” He paused. “Aandred, I was. A glorious, wicked name once. Now? Meaningless…” His voice had fallen to a wistful whisper.

“I’d almost forgotten it,” he lied.

Part of me wishes that we had found out Aandred’s name at the same time that he reveals it to Sundee, making for a more literary experience as we journey with him from his mindless existence as Huntsman through to his rediscovery of his sense of self. But knowing he has that last vestige of humanity and has kept it tamped down in spite of Droam’s best efforts makes him a more interesting character. It makes his conversion to Sundee’s cause far more believable, too.

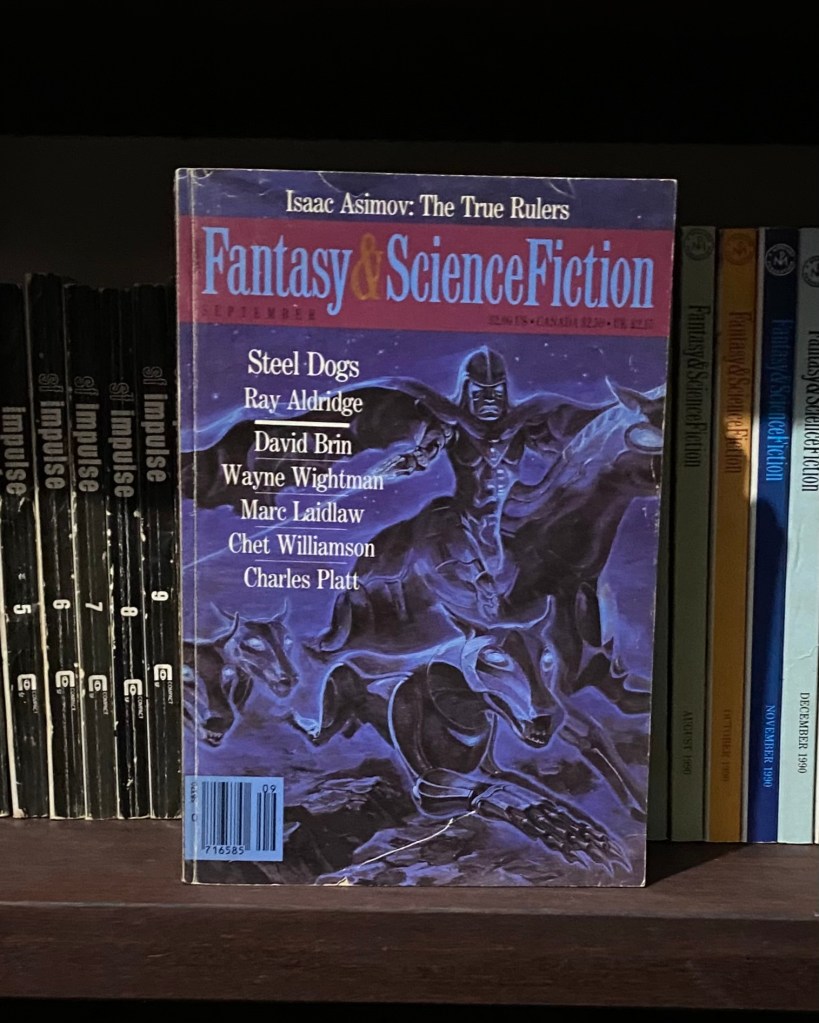

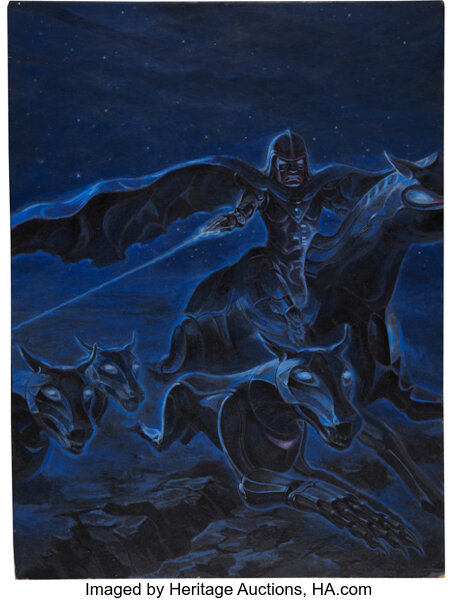

I first read it in the September 1989 issue of The Magazine Of Fantasy And Science Fiction (hereafter referred to as F&SF). “Steel Dogs” was the cover story. The cover, as the photo above shows, is dramatic and eye-catching but it the flaws are readily exposed by the presence of words: you can see more readily that something is slightly off about the size of Aandred’s arms. However, when you take the typesetting away from it, it’s a completely different picture, being far more atmospheric and dramatic.

“Steel Dogs” was also the first story in that issue.

It was also the first issue of that magazine I had read.

I was no stranger to magazine fiction, though: I had been reading Omni for a couple of years by this point and had really liked its mix of fiction with articles about science and, er, …science-adjacent topics (“woo” or “woo-woo” were the accepted terms back then although they have fallen into disfavour since then). I’d also read a heap of anthologies and knew a little bit about the history of SF and the major part that short stories had played in that. But F&SF (est. 1949) was something that I really wasn’t that familiar with beyond its reputation, which was for genre fiction of a more literary bent than you might find in places like Analog or Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. Indeed, when I looked at the copyright pages of many of my favourite stories, it was clear that I was already part of the audience for F&SF.

Let’s look briefly at a couple of the other stories.

The story immediately following “Steel Dogs” is “How Hamster Loved The Actroid With Garbo’s Eyes” by Chet Williamson. I loved this story almost as much “Steel Dogs” but it hasn’t aged terribly well. It’s the story of a computer programmer who develops a new way of generating CG characters and settings for movies (he calls it “comgen” because we loved our portmanteau words in SF back then). He creates a female model who is an accomplished actress but whom he them falls in love with. What follows is an odd look at what people will do to be with – or even become – the person they love. It’s a lot of fun, but the bit that has aged poorly is the author’s idea that people will accept CG version of beloved actors in movies they never made in their lifetimes…

I sought out several of Williamson’s novels after this and enjoyed them a lot but he’s not an author who has stayed with me, unfortunately: his style was one that I outgrew but he is still worth seeking out.

The issue closed with a story by David Brin: “Privacy.” This was a bit of dealbreaker for me when deciding to buy the magazine as I was mainlining a lot of Brin’s work at the time and a new short story by him seemed looked to be a really cool thing to read. It turned out that it was a fairly self-contained extract from his next novel, Earth, but it dealt with some interesting ideas that were remarkably prescient: it’s about a young man in a climate-ravaged near-future (roughly 13 years away from this date of writing, depressingly enough) dealing with feelings of inadequacy in the face of the society he is expecting to be a part of when he graduates from high school. What is interesting is the way that the story manages to predict things like augmented reality, social media, and the plight of those who have simply just not kept up with the pace of technology (The novel also gets points for using “Boomer” as an insult in the days when that generation were just starting to have mid-life crises).

There were also some lively and opinionated book reviews by Algis Budrys and Orson Scott Card (just a few years before he alienated most of his audience), and a science column by Isaac Asimov. I really felt that there was a tremendous vitality to the magazine, so I naturally went back for more, and was a regular reader for the next few years, and have been an occasional reader and subscriber ever since then. In recent years, the publication has been less regular than fans might like and we haven’t seen a new issue in several months. I’m hoping that this is a hiccup rather than an end to what is a cherished publication.

During my writing career, I also submitted a couple of stories to them. Alas, they were not accepted but I treasure the rejection letters.

But “Steel Dogs” was what kept me going back issue after issue: no matter how far I have come in my appreciation of literature and storytelling, it remains a highwater mark in how to grab a reader’s attention.

It doesn’t do anything that you might describe as “new” or “revolutionary”, but it’s inventive and dark and wonderfully told. It’s a good story told well, with a solid foundation to it and with a small but memorable cast of characters. The climax is thrilling and the conclusion thoughtful. It was one of those stories that made me shiver with delight at everything that happened; that made the hairs on the back of my neck rise up in excitement.

Aldridge wrote other stories with similar themes – his Dilvermoon stories are well worth looking out for if you can find them, as are “The Cold Cage” and the poignant “We Were Butterflies” – but “Steel Dogs” remains my favourite of his too-small body of work.

You can find out more about Ray Aldridge at https://www.worldswithoutend.com/author.asp?ID=4464