Seymour has been sent to live with a friend of his mother for the summer due to his parents having an acrimonious breakup, and he isn’t enjoying it. Instructed to stay inside when Thelma (his guardian) is at work, he one day rebels and winds up in the shabby accommodation of Angie, a vivacious young woman who, Seymour later discovers, has problems of her own…

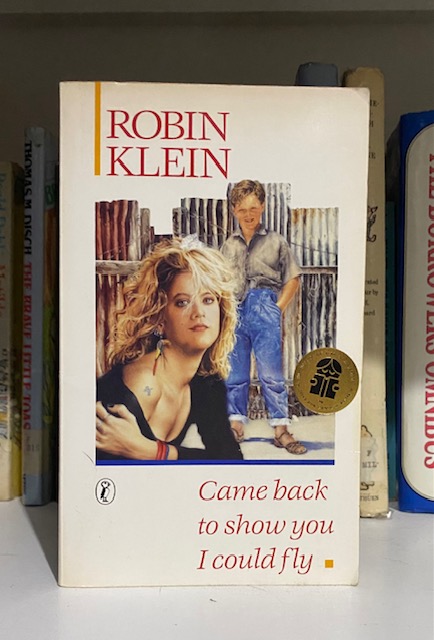

Came Back To Show You I Could Fly (1989) by Robin Klein is what’s known as a social novel. Somewhat out of fashion these days, they were a genre of story that talked about contemporary issues, ranging from divorce to domestic violence to drug addiction to… well, anything the author may have seen some sort of angle for a story in. They were ubiquitous from the 1960s through to the early 1990s, and – despite often reading like an updated version of Victorian “Literature Of Improvement” – dominated a lot of awards and recommendation lists.

In Australia, being able to sample a lot of titles from around the world (but usually just the U.K., U.S. and Canada) meant that our authors were able to see the sorts of stories that worked and adapt their themes to our own history and circumstances.

Robin Klein has a particular genius for this sort of story. A national treasure here in Australia, her books (ostensibly written for children but enjoyable at any age) are uniformly superb. From the whimsy of the Thing series, to the raucous comedy of Hating Alison Ashley, through to the grim realism of People Might Hear You, her books are united by the fact that they are intelligent, funny and highly relatable.

Came Back To Show You I Could Fly is no exception. It won the “Human Rights Award: Children’s Book” when it was first released in 1989 and was the Children’s Book Council of Australia’s Book of the Year in 1990. It was also filmed in 1993 under the title Say A Little Prayer. The title change was due to a copyright issue with the song that the title takes its name from (“From The Inside” from Marcia Hines’s debut album Marcia Shines (1975)). I haven’t seen the movie bur it had a middling reception on release.

I first read it in 1991. I was about halfway through my teaching degree, and I was trying to keep up with what was being released in the field I was studying in.

(Oh, all right: I was just after an excuse to buy more books and not feel like I should be studying.)

Anyway, I loved it. Seymour was a hugely relatable character for me and Angie… well, I was conflicted about Angie.

Because I’d known people like Angie: drug addicts and pretty criminals who get away with nearly everything due to a magnetic personality and a winning smile. And I reacted a lot like the people in her circle did to her: with distrust and fear. Because I knew what they were like. Once the drugs dominated their lives, nothing else mattered. Friends, family, work – it was all thrown away and discarded except where it could be exploited to get more access to drugs. People I had known for ages became different, and because I wasn’t interested in doing drugs with them or – more frequently – had no money to spend on them, I was increasingly left out of their social circles. And their behaviour would alienate me so that I really had no interest in keeping up with them, anyway.

So, when Angie crops up in the story and meets Seymour:

She was the most beautiful person he’d ever seen in his life. Her large gentle eyes were the colour of rain-wet lichen, fringed with dark lashes that curled back upon themselves, and although she was a grown-up, she wasn’t really threatening in any way. She just lay there, soaking up the sun, quiet and calm and easy-going…

I wasn’t prepared to like her.

In Seymour’s defence, he has just been scared by some of his new neighbours and has run into the first open door he found in order to escape it, so he isn’t in the best space to be a good judge of character.

So I was prepared to judge Angie unkindly, especially after her interactions with all the characters in the book that aren’t Seymour.

And her early behaviour with him tends to support this: she piles on the charm for him, but forgets when he’s coming over or that she’s promised to take him places; she expects an eleven-year-old to help out with tram and train fares; she lies to him about her setbacks, blaming other people more easily than admitting her own fault in even simple issues.

But Seymour is what the Angie’s in my own life didn’t have: somebody nonjudgemental who didn’t want to let her down and just wanted to be her friend. And who eventually has the courage to tell them when they’re being selfish and parasitic.

Because even when Seymour finally realises that Angie is on drugs, he still believes in her. Even after he watches her family taking her away to hospital…

Seymour watched it all and raged silently, “All her family, they’re so rotten and stuck up, you’ve only got to look at them. They don’t give a stuff about Angie…

But he knew that actually, that wasn’t the truth of it at all. He’d caught a glimpse of their faces as they carried Angie out to the car, and what he’d witnessed there was a kind of raw and hopeless grief.

… he is still hopeful that Angie is capable of redemption.

It’s not until he visits her in hospital and she begins to lie to him about what’s wrong with her and why she’s like she is, that he realises just how dire a situation she’s in.

It’s because he’s reminded of his mother.

Let’s backtrack a little…

Seymour’s mother has dropped him off with a friend she knows through her church, ostensibly to protect Seymour from his father, who is currently estranged from her. Seymour is bewildered by the picture that his mother paints of her spouse, making Thelma (her friend) worry that her ward could be abducted off the street by a vicious predator. It’s reinforced by her visit partway through the book:

First she opened the door a crack and peered through, then went dramatically to the gate to check that his father wasn’t lurking about on Victoria Road.

However, Seymour remembers his father differently:

… a memory edged into his mind, of the little fold-down table in the caravan and a newspaper spread out at the employment ads, some of them ringed with pencil. Seymour… had watched his father’s hands go up to his temples, and the worry lines across his forehead deepen into something like despair.

His mother, he realises, manufactures a lot of drama to make her otherwise tedious life more interesting and his father – by suffering from the tensions of unemployment and poverty – plays right into it when his circumstances become even more fraught.

And when Angie begins to sound like his mother – blaming everyone but herself for her problems – Seymour decides to cut his losses and, after a row with her in her rehab ward, leaves her.

It comes near the end of the book, and it could have been a quite moving but depressing ending. But there’s an epilogue, wherein Angie writes to Seymour and they begin a tentative correspondence, beginning to heal their fractured friendship, ending on a note of hope.

And this epilogue bookends a lot of other letters, notes and ephemera scattered throughout the book, mostly between chapters. They’re letters, largely from Angie to the people in her life, with occasional replies from them, detailing just how badly she has treated them and why they don’t want to have anything more to do with her.

But there’s also some journal entries from Angie, or some kind of inner monologue showing that she does want to come clean and is trying hard to stay off the drugs. We also get glimpses of her life before she met Seymour, showing that she is trying to move on and that she is working at improving herself. These contrast fantastically with the main story which is entirely told from Seymour’s perspective, lending the reader more sympathy for Angie’s plight. Her story told through the lens of a naïve eleven-year-old is often bewildering and full of dark gaps that we don’t want Seymour looking into too closely. Angie’s side of the story lets us see aspects of her life that she herself doesn’t want to dwell on or go back to, lending credence to her history and the way that her family and friends feel about her.

Which is what makes this story nearly perfect to me. We don’t know if Angie will stay clean, we don’t know if Seymour’s parents will reconcile, all we know is that they’ve turned a corner in their lives and found someone they can rely on. The rest is up to them.

You can find out more about Robin Klein at https://lettersfromrobin.com/