Usually I start these pieces with a quick precis of the plot. But since this month’s entry is an anthology, that’s really quite difficult to do. What I’m going to do instead is start with a memory…

Across social media and blogs around the world, you’ll sometimes find readers reminiscing about Scholastic Books. Scholastic was a publication started in 1920 by Maurice R Robinson. Their first magazine was a leaflet that was distributed to high schools detailing sports and social activities. It gradually expanded until today where it has become a multimedia empire worth around half a billion dollars a year.

But for a lot of people, what they remember is the Book Club and, latterly, the Book Fairs.

If you don’t know, the Book Fairs are a travelling store that go around schools acting as a fundraiser as well as a bookshop; the school I teach at holds one every year. We also take part in the Book Club, a sort-of-monthly event wherein catalogues are delivered to classrooms and students (and sometimes teachers, I’m not ashamed to admit) can select what books or literary-based artifacts they would like and a couple of weeks later, it arrives!

I was a huge fan of the Book Club as a child, ordering a ton of books from it, very few of which I still have, alas. The subject of this post is one such piece of ephemera.

So, let’s take a look…

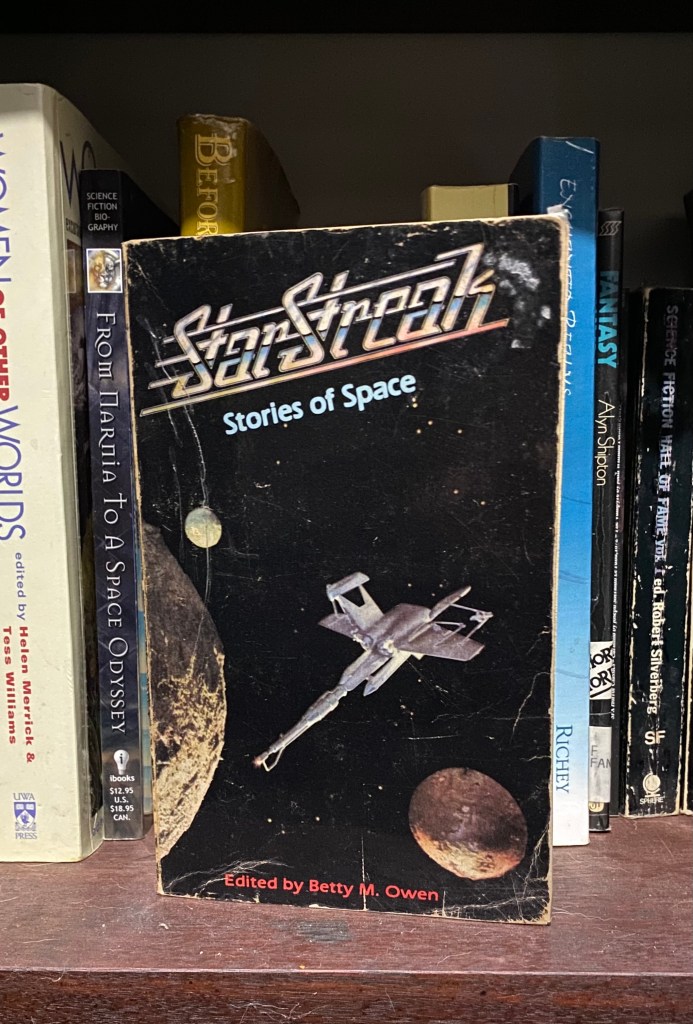

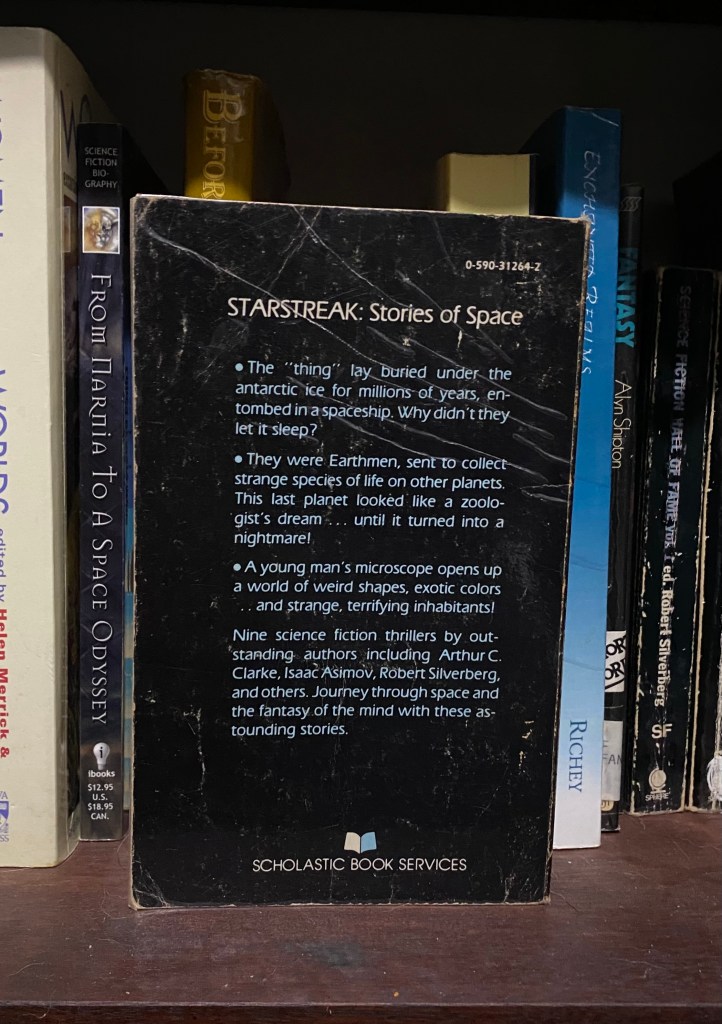

StarStreak: Stories Of Space (1979) is an anthology edited by Betty M. Owen. Owen was an editor at Scholastic who created several anthologies across a wide variety of genres for Scholastic, as well as their original line of magazines. She ran the entire gamut of editing, from what I’ve been able to find out, taking part in collating stories for publication, proofreading, accounting and communicating with authors. She has left a very thin trace of herself across the books she edited, though, by not including any kind of introduction or preamble to her books; letting, rather, the stories speak for themselves. However, looking at the contents tables of her anthologies, you get the sense that she believed young people deserved to be exposed to the widest range of stories by the most eclectic bunch of writers possible. Even when compared to the erudite selections made by Robert Arthur on behalf of Alfred Hitchcock for the endless collections put out under his name, these are damned good anthologies.

StarStreak is no exception. There are only nine stories in it so we’ll discuss each one as we go.

The first is John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” You might know it from a 1982 film adaptation of a different name. I didn’t know who Campbell was in 1979 but I found out within a year or two of reading this that he was most famous for being the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, a magazine that goes under the name of Analog these day. The blurb on the back of the book summarises the story thusly:

The “thing” lay buried under the Antarctic ice for millions of years, entombed in a spaceship. Why didn’t they let it sleep?

I’m not ashamed to admit that when I saw a poster for The Thing a couple of years later and read the first reviews of it, I thought it was most prescient of Owen to use the quote marks in the way she had three years before the film had been released. It wasn’t until a little while later that I realised she had probably been referencing the 1951 version of the story directed by Christian Nyby under the title The Thing From Another World. When I eventually got to a position where I was able to compare all three of them, I was amazed at just how faithful the 1982 film is to the original story, which is still quite gripping even now, 87 years after it was first published.

(This version of it, by the way, is an extended version of the original short story… but it’s also an abridged version of a longer novel, which was published in 2018. It’s become a hugely influential tale and you can see its fingerprints all across various genres.)

“Who Goes There?” takes up 92 of StarStreak’s 216 pages. The next longest story, “The Rotifers”, only takes up 19, making the rest of the anthology feel composed of bite-sized chunks.

But Robert Silverberg comes next, with his story, “Collecting Team.” It’s a fairly traditional story about a team of biologists who land on a planet filled with a massive variety of life that shouldn’t all exist in the same place. It’s not until they realise that they are finding it harder and harder to leave the planet that they surmise what has happened to them…

At the time, I was quite impressed with this story. It wasn’t until I became a little more widely read that I realised that the theme was pretty tired even by the time of its original publication (1957) – The Twilight Zone even did a variant of it in its first season two years later, starring Roddie McDowall. However, Silverberg manages to inject some excitement and mystery into it, turning it into a pleasant read.

The third story is a short piece by Arthur C. Clarke called “The Haunted Space suit.” It’s the tale of a hardboiled astronaut who has been called in to identify and tag a piece of space junk sometime in the near future. It’s not until he’s out in space, that he realises that the last person to use the suit died in it. And that it might be haunted.

Look, I love Arthur C. Clarke. He wrote some brilliant novels and is one of the great explainers of science. But some of his short stories are terrible: a lot of them use obscure scientific facts or theories to create a punchline to an already weak story. This one doesn’t even do that: it’s interesting and atmospheric but the denouement is straight out of Scooby-doo, despite pre-dating it by about seven years. But nine-year-old me lapped it up and immediately went out to find more stories by Clarke, reinforced by his other story in this volume. So I guess it worked.

The fourth story is “Condition Of Employment” by Clifford Simak. This is the tale of a spaceman desperately seeking work that gets him back out into space and home to Mars, which he swears he will never leave again. However, once he gets there he remembers that he’s been treated to be homesick, because it’s the only way that astronauts can be persuaded to go back into space, due to the terrible conditions aboard spaceships.

This was one of the first stories I had read that dealt with the psychological possibilities of space travel. It took me a few years before I properly understood what it was trying to say because… well, I was only 9 at the time. But I remember being captivated by the idea of being so hung up on getting away to somewhere else that you would risk anything to get there, and the way that Simak conveyed that through his destitute astronaut and his weird odyssey.

The fifth story, “After The Sirens”, is the only science fiction story by Canadian author Hugh Hood, more famous for his 12-volume New Age sequence of novels, published between 1975 and 2000). It’s a gripping tale of a young couple and their child who are awakened by an alert warning them of nuclear conflict. It’s probably the most affecting and evocative story in the collection, dealing as it does with the possibility of nuclear war, which was all over the media in my young life at the time. The details, such as how the family took shelter, the way the nuclear blast pulverised their house and town, as well as the detail in the last sentence that

They were the seventh, eighth and ninth living persons to be brought there after the sirens.

really brought home to me the absolute terror of what a nuclear conflict could mean. It seems rather dated now but it’s still quite impactful in what it does.

That impact is only ruined by the next story, the only real dud in the entire collection. “The Spaceman Cometh” by Henry Gregor Felsen. Felsen was a bestselling author of many books in the genre that we would now call YA, including Hot Rod, a novel read by thousands of children in its time, including Ben Hanscomb in the 1958 sections of Stephen King’s IT. (Ben enjoys it, by the way: he finds it “Not too shabby at all.”) Felsen is a talented writer and manages to convey the main ideas of this story well.

It’s just that it’s not very good. It’s the story of Ex-my-ex, an Adnaxian space pilot who has fled the war engulfing his home planet and escaped to Earth where he has adopted a human guise, married a local girl and started a family. Then, one day, he encounters an Adnaxian ship piloted by his old university professor My-ex-ex, who has been searching for him. Ex-my-ex – or Henry, as he is now known – decides to show his old teacher around, and…

… it’s witty and smart, but it’s terrible science fiction. For example when… Henry… reverts back to his Adnaxian form he is still in his uniform, inferring that he has been in it the entire time he was on Earth…

…

… He has children, for crying out loud! Ignoring the impossibility of cross-species fertilisation, does that mean he was in uniform when he and his wife conceived them?!

This, like Hugh Hood’s story, was Felsen’s only foray into science fiction, apart from a juvenile novel called The Boy Who Discovered The Earth (“juvenile” meaning the genre rather than the style… oh, hell, who am I kidding?). “The Spaceman Cometh” reads like somebody has tried to write a story in a genre they aren’t familiar with while only researching it through the sneeriest and most general of reviews and surveys. It features some rather clever observations on Earth (specifically North American) culture and the paradoxes within it (which you might guess from the literary allusion in the title). But it’s also patronising and twee in a lot of places – the world is saved by a mother-in-law joke, for pity’s sake.

Anyway, on to the next tale.

“The Nine Billion Names Of God” is a bona fide classic and probably the best-known story in this anthology – I’d already read it somewhere else before seeing it here. It’s written by Arthur C. Clarke and is an infinitely superior piece to “The Haunted Spacesuit” from earlier in the collection.

It’s the story of a team of computer engineers who have been hired by a Tibetan monastery to calculate all the possible permutations of God’s name, after which, God’s work will apparently be done. Like a lot of Clarke’s work, there is a rather astonishing display of knowledge about the topic on display and a climax that is more of a punchline than a real ending. However, the simple, playful elegance of

overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.

is a wonderful way to end a story.

It hasn’t aged well, of course: Tibetan monks might not be as interested in God as British SF writers might think (although the story treats the characters with some sensitivity and respect rather than being patronising or racist), and there are some elements of computer science that were hideously dated by 1979 (not I knew or cared) let alone here in 2025.

But it is a wonderful tale.

Another wonderful tale is Robert Abernathy’s “The Rotifers.” Abernathy published a couple of dozen stories during the 1940s and 50s. This is possibly his most famous one, but several others were anthologised a few times. It’s the story of Henry Chatham, a father who buys his inquisitive son a microscope so that he can further investigate the marvels of the natural world. However, the natural world starts looking back…

This is more of a borderline horror/weird fiction story, but it works. I remember myself being a little freaked out by its ending – in which Henry senses the anger of the microscopic creatures that are beginning to band together to fight against the human world they have just discovered – and immediately trying to find more stories that would do the same thing again.

Fortunately, I found something in the same eerie ballpark in the next, and final, story: Isaac Asimov’s “Does A Bee Care?” This is the tale of Kane, a strange being who sparks inspiration in those around him, and who has inveigled himself into a minor role preparing a spacecraft for launch. What the other workers on the project don’t realise is that Kane has built a place for himself aboard the craft so that he can escape the world he has grown into maturity on and become something more than the human he appears to be.

Middle-aged me recognises that this is a minor work by Asimov exploring a theme that was used by some fairly lazy writers not long after this was originally published (1957), but (again) nine-year-old me lapped it up. But this was real mind-expanding stuff for me, and when I finally got around to reading Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker many years later, part of me felt like I was very familiar ground.

So that’s a brief recount of StarStreak: Stories Of Space. I loved this collection. I read and reread it avidly for several years until I found many other stories that exceeded the limits of it. Even the cover, with its dodgy spaceship and papier-mache planets got me excited. However, I eventually lost it in a move and didn’t think too much more about it. But when I saw a copy of it in a second-hand shop nearly twenty years later, I instantly grabbed it up, hoping that the magic would still be there.

To a large extent, it was: Owen’s skill as an editor was not in picking the best examples of stories, but in picking the ones that would be the most evocative of an idea, that would be the most accessible to the audience.

Namely, nine-year-old me.

Every one of the stories in this collection sparked something in me that made me go and search out more like it – even “The Spaceman Cometh”, which at least had the excuse that it was trying to make a (fairly hackneyed) comment about the bloodthirsty nature of mankind. Each one of them reached a part of me that was hungering for some kind of expression about making sense of the unknown, harsh universe that surrounds us.

And, fortunately, each one was written in a way that captivated me.

Anthologies can be tricky: not every story can be a winner, and it’s an editor’s hope that there will be enough stories that intrigue a reader that they will overlook any potential duds. Anthologies written to a theme are often simpler, but even then you run the risk of having a narrower field of stories to choose from. What Owen produced in StarStreak; Stories Of Space is a mixed bag of successes. On the one hand, the contents don’t really match the title – there are nine stories here, but only four of them take place in space (while one of them finds the characters completely planet-bound!) – but I didn’t really care: there was enough of the old “sensawunda” (as it used to be known) to make me just keep reading and not worry about the thematic application of the anthology’s title to its contents. Which, to me, made it a success.

When I was in my first year of university, I came across another of her anthologies, simply titled 11 Great Horror Stories. This featured writers as varied as H. P. Lovecraft, Jack Finney, and Edgar Allan Poe. I’m not sure how successful it was commercially – it was published in 1970, several years before Horror began to really explode as a genre, and several of these stories are borderline Fantasy or SF as well, but I lapped it up again, simply because of the editor’s name and my fond memories of StarStreak.

Which, “The Spaceman Cometh” notwithstanding, makes it a success to me: this was a stepping stone on my journey to becoming the reader I am today.

You can find out more about Betty M. Owen’s books at https://www.librarything.com/author/owenbettym