Back in 1588, England was invaded by the Spanish Armada. The ungodly Church of England – and the unnatural Queen Elizabeth who headed it – were thrown down and Catholicism was restored as the kingdom’s only religion. But in the years that followed, natural philosophy began a very slow rebellion and the world began a slow change back to what was and what could have been…

I’m not a big fan of Alternate History novels. I think they are clever thinking activities in what might have happened if something else had occurred instead of what we regard as the regular course of history. However, too often the history just becomes an exercise in guessing what may have taken place which is a lot of fun, but often falls down because the author has done some astonishing research on what existed at the time in one part of the world, but not what existed elsewhere. And they also become way too attached to certain parts of history and refuse to let them go.

As an example, Susannah Clarke’s novel Jonathan Strange And Mr Norrell exists in an alternate Britain in which magic exists. There are an astonishing number of points where what happened there differs from what happened here. And yet, Nelson still exists as a major military figure; Napoleon is still the Emperor of France; and Lord Byron is still a colossal dick.

Terry Pratchett’s Nation exists in a world that took a clear divergence from our own history but characters still quote Jane Austen, Shakespeare and Darwin.

These are two books that I adore, but little details like that crop up and, while they don’t detract from my overall love of them, they do make my investment of belief a little harder to take. When an alt-hist novel (as they are known) is more successful, I find, it takes its divergent point as being a little more recent than centuries before. Philip K. Dick’s The Man In The High Castle (in which the Axis powers won World War II) is probably the most famous of this sort.

Keith Roberts’s (1935- 2000) mosaic novel Pavane suffers from very little of this sort of thing. The world inhabited by his characters is very similar to our own: slower, a little more oppressive perhaps, a little more backward, but still recognizable…

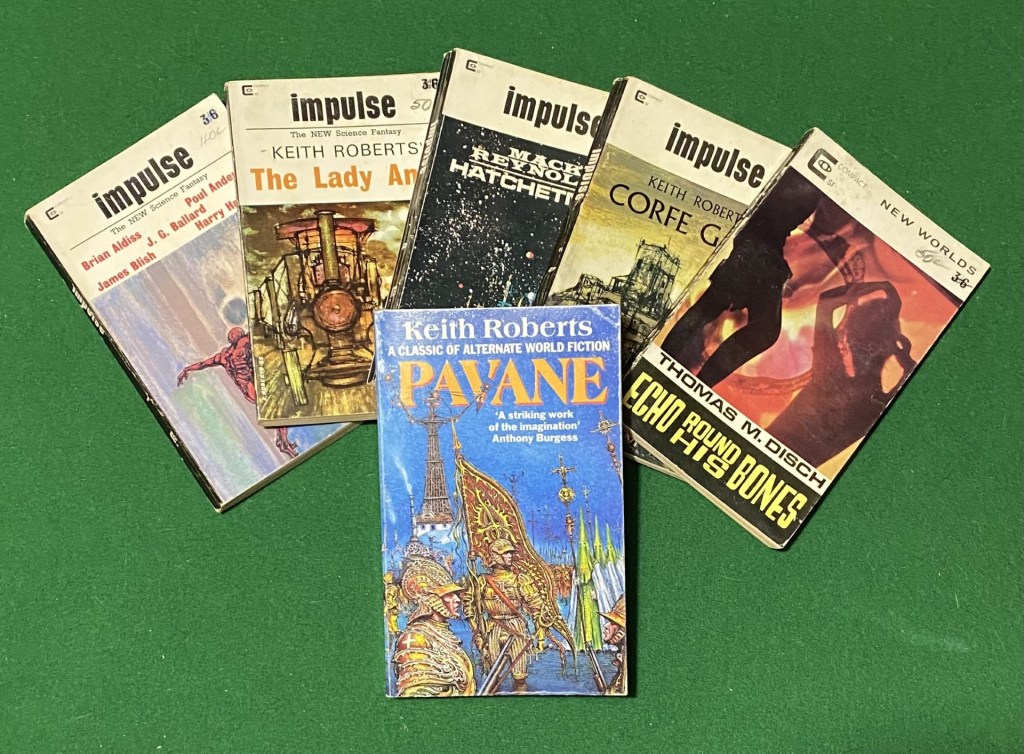

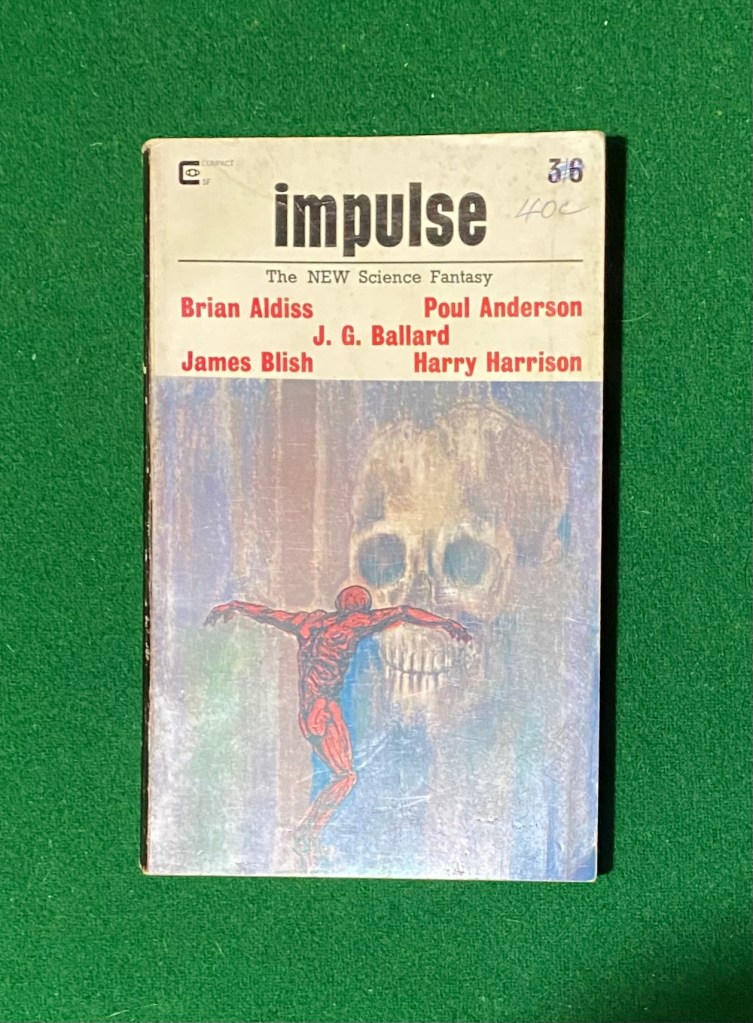

It was first published in New Worlds and Impulse (a magazine that Roberts edited) before appearing as a novel in its own right in 1968. Each story takes place in a different time with characters linked by family, place and technology so that the overall themes and ideas of the story become more apparent as time goes on.

The first story, “The Lady Margaret” (originally published as “The Lady Anne” in Impulse 2, April 1966) is about Jesse Strange, latest in a line of hauliers. His joy is The Lady Anne/Margaret, a powerful roadtrain and the basis of his family’s fortune. On a lonely freight run, Jesse runs into an old friend, who he later discovers is a highwayman. Jesse is prepared for his inevitable betrayal, though. This story sets the tone for the rest of the novel: despite being set in the novel’s year of publication, 1968 (1965 in Impulse), it hints at a more pastoral England, where life is moving a little slower. It bears little resemblance to the 1968 we are familiar with, with trains regarded as the giants of transport rather than the just one of many ways of getting about.

The second story, “The Signaller” (Impulse 1, 1966) is told in flashback. It’s the short life of Rafe Bigland, a member of the Guild Of Signallers, the men who work the lonely semaphore stations, transmitting information across the land. We follow Rafe from him spying on the semaphores as a small child, to him learning the codes and secrets of the Guild and through his short career as a Signaller in his own right. It’s here that we first learn that all might not be right in Roberts’s pastoral, backward England…

The next story, “The White Boat” (New Worlds, December 1966) gives us the exploits of Becky, a fisher girl, fascinated by a white boat that occasionally sails into the harbour of her hometown. When she boldly goes aboard it she is convinced that the master of the ship and his crew are just smugglers, and the story ends with the white boat escaping the authorities after a brief chase and battle on the water. However, some of the things she has seen aboard the boat hint at its origins being from further away than she might have imagined…

Story number four is “Brother John” (Impulse 3, May 1966). Brother John is a young priest who is engaged on the work of the Church in its Holy Inquisition. But after witnessing the work of his colleagues he becomes disillusioned with the Church and wanders the land preaching rebellion until his final confrontation with the Church and its secular forces.

The fifth story, “Lords And Ladies” (Impulse 4, June 1966) goes back in a way, to the first story, with Margaret (named Anne in the magazine edition), niece to Jesse Strange. Jesse, sadly, is dying and we follow Margaret as she befriends the son of a well-born family, before becoming disgraced by him, then having her own supernatural encounter – though less brutal than Rafe’s.

The final story, Corfe Gate (Impulse 5, July 1966) follows Margaret’s daughter, the Lady Eleanor, as she rebels against the Church. While leading this fight she also discovers that the Guild Of signallers have progressed further along another path than she had ever dreamed…

There follows a Coda, in which we learn the truth of the various otherworldly encounters the characters in this novel have had: that there was a plot to travel back in time and slow progress so that mankind could mature before progressing:

Did she oppress? Did she hang and burn? A little, yes. But there was no Belsen, no Buchenwald. No Passchendaele.

As an ending it feels a little glib, a little too much “ends justifying the means.” But it doesn’t take away from the power of the rest of the novel, or the wonderful ideas that it sheds like dog hair throughout the length of it.

I first read Pavane last century. I was amazed at the vivid writing, the strong characterizations and images that Roberts was able to exert upon his story. I also loved it for the relevance of one particular plot element.

Semaphores.

Semaphore stations were a technology coming into their own a couple of hundred years before I was born. Though quickly supplanted by the telegraph, it was an elegant form of communication that took a known system – communication by flags and beacons – and transformed it into something elegant and futuristic (for the time, obviously).

There were semaphore stations all across south-eastern Tasmania when I was growing up. No longer in use, of course, but their sleek masts and station houses were a reminder of a time gone by.

I used them as a technological development in my first novel, a telecommunication device favoured by my main character as he strove to transform the world that he found himself in unwillingly into something more familiar. Not long afterwards, Sir Terry Pratchett utilized a smarter version of it in The Fifth Elephant, the 24th Discworld novel, so I knew that it was definitely a good idea.

But I read Pavane while in the process of writing my own book and it became a small touchstone to me that, while my idea may not have been original, it was good enough that someone else had had it before me and used it in a thematically similar way that I wasn’t deliberately ripping off.

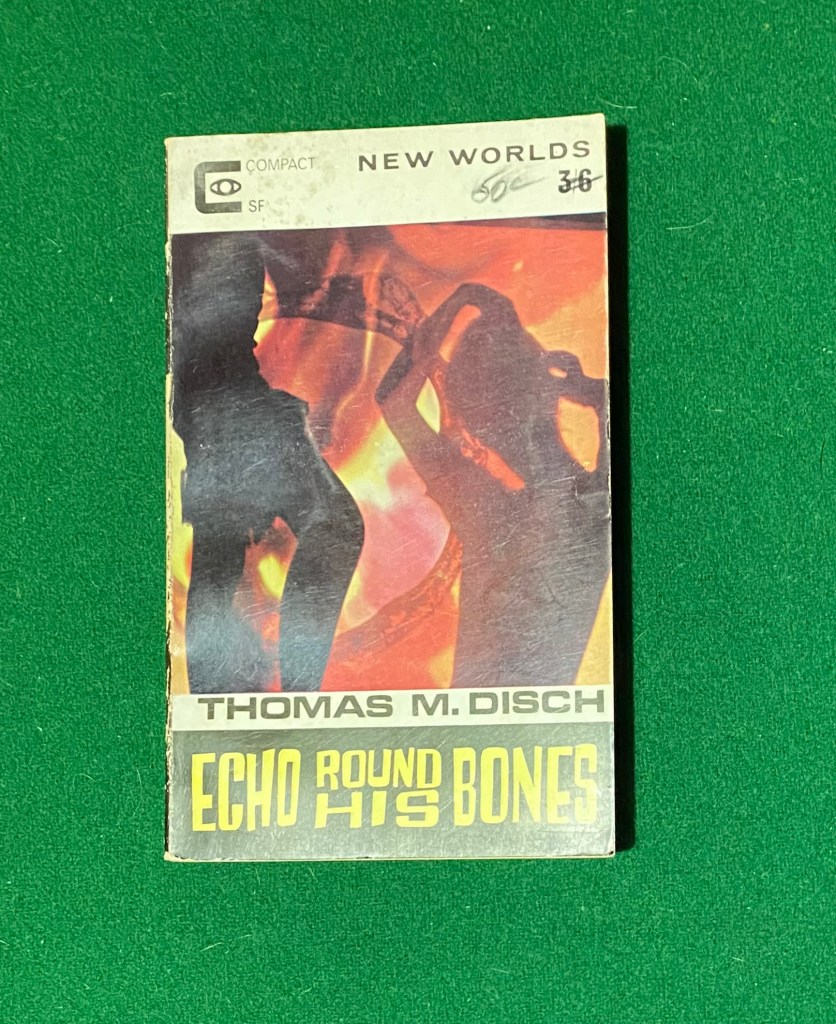

I recently developed a refreshed interest in the novel when I stumbled upon a big box of old SF magazines from the 1950s and 60s. It was mostly New Worlds and its sister magazine, Science Fantasy, which later became Impulse.

These magazines featured a lot of authors that I already loved, as well as a bunch of new ones that I have come to admire, not the least of which was the late and great Thomas Burnett Swann. But Keith Roberts was probably one of the major rediscoveries: these old magazines also featured the serialization of his wonderfully bonkers disaster novel The Furies, as well as a host of stories about the young witch Anita.

But it was the serialization of Pavane that intrigued me the most. Because the stories were published in a different order to what we eventually got in the book. The name change – Anne to Margaret – I can forgive because that doesn’t change much about the themes and central ideas… but the order of the stories was intriguing, especially since most of them were published in a magazine that Roberts had an editorial interest in. It’s intriguing to consider a version of the story where we meet Rafe and share his experiences of the otherworldly before being plunged into the more mundane world of Jesse Strange and his roadtrain. Likewise, with “The White Boat” being published last, given its hints at the world that Eleanor and her contemporaries live in, makes it a more fascinating – and possibly less ambiguous – conclusion to a wonderful set of stories.

What we have, though, is a wonderful story that deserves its reputation and fame – in any world.

You can find out more about Keith Roberts here: https://www.solaris-books.co.uk/Roberts/