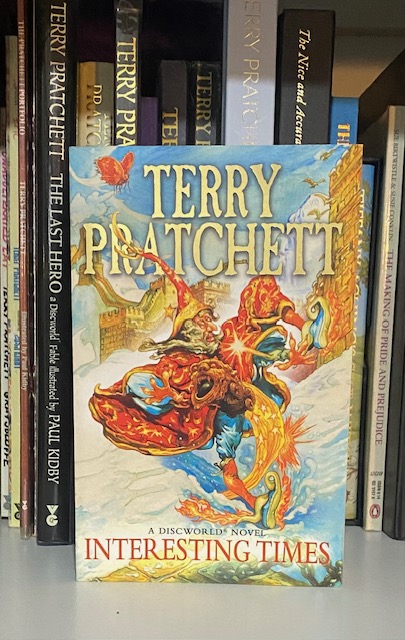

When we last saw Rincewind, he was walking nonchalantly, calmly and fast out of the Disc’s version of Hell, accompanied by Eric, the titular demonologist of that adventure. Since then he has been living on a tropical island leading a dull and uneventful life where his only concern is where his next meal is going to be coming from.

However, things are not going well back in Ankh-Morpork: Lord Vetinari has received a summons from the Agatean Empire, all the way across the Disc on the Counterweight Continent. Vetinari claims to have not had a message from them for about ten years. The message reads, “Send Us Instantly The Great Wizzard.”

Mustrum Ridcully, Archchancellor of Unseen University, is baffled at first. But he gathers from his colleagues that during the time of the Sourcerer – although none of them were actually present then, you understand – there was a practitioner of magic (for a given value of “practitioner”, of course) who spelt the word in that unique way (despite Ridcully not being Archchancellor until some time after the events of that book). Naturally, the faculty of the university, under the leadership of Ridcully and the actual guidance of Ponder Stibbons have summoned Rincewind (by magic) and sent him (again, by magic) to the Agatean Empire, which is currently in a state of revolution caused by the publication of the revolutionary text, What I Did On My Holidays.

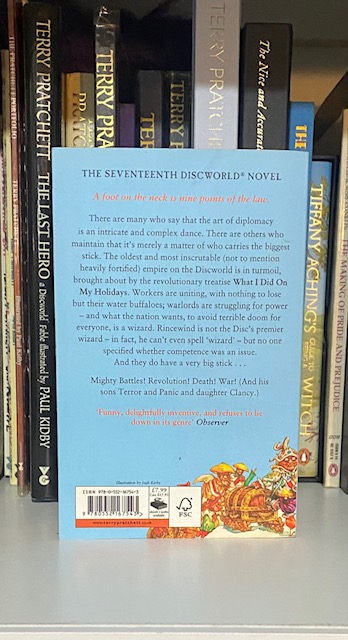

Interesting Times is a rarity among a lot of Discworld fans: it’s quite competently written, funny as hell, but it’s not very highly regarded. Not in the way that The Colour Of Magic and The Light Fantastic aren’t very well-thought-of (because they aren’t considered to be as well written as the books that follow, and that’s the opinion of Sir Terry himself). No, it’s regarded a little shadily because it’s probably the most racist of all Sir Terry’s works.

Not intentionally, of course, and not maliciously but there are quite a few moments that do not linger fondly in the memory.

Again, though, to appreciate the full picture, we are going to need a little bit of context.

Chinoiserie, or fantastic tales set in some imagined version of China, have a long and storied history in Fantasy. Many authors – most famously, Ernest Bramagh and Barry Hughart, have used a version of Chinese “history” to tell a story that they wanted to tell. More recently, Guy Gavriel Kay attempted a respectable – and respectful – historical fantasy in a version of China with Under Heaven and River Of Stars.

However, for every acclaimed tale that treats the historical context seriously, you have a dozen authors who persist in stereotypes. Sax Rohmer’s supervillain Fu Manchu is probably the most famous; while on the other hand the detective Charlie Chan, created by Earl Derr Biggers as an antidote to Fu Manchu, featured in an increasing number of movies, TV shows and radio programs throughout the middle of the Twentieth Century, most successfully when portrayed by non-Asian actors.

Public opinion about how these characters were portrayed has contributed to the fact that there have been no new stories or movies in wide circulation since the early 1980s.

Other portrayals of “inscrutable” orientals have also dropped off our cultural radar. Doctor Who went up against Li H’sen Chang, a stage magician, in the story serving the treacherous Magnus Greel in The Talons Of Weng-Chiang which was rather highly-regarded until recent years when it became more widely-known that the actor portraying Chang was not Asian. This story does feature some interesting commentary about how the different cultures interact, but it was let down by that central piece of casting as well as some quite terribly-aged dialogue placed into the mouth of The Doctor, a usually quite moral and decent character.

And don’t get me started on The Celestial Toymaker.

Note also that very few of these authors have Chinese backgrounds.

Anyway, by the 1980s, Chinoiserie was starting to make a comeback, possibly due to the popularity of Cyberpunk which almost fetishised East Asian, particularly Japanese, culture. Fantasy quickly caught up with several fictional races standing in for Chinese and Mongolian cultures. Many of them were embarrassingly poor – David Gemmell’s Nadir tribes in his Drenai novels were saved only by some astute observations on the nature of racism as well as some wonderful characters – and focused heavily on matters of rigid honour and class.

You can argue that Pratchett (yes, we’ve finally gotten back to him) had ben ahead of the crowd all along: Twoflower (who makes a welcome return in this book) was always a parody of a particular type of tourist in his original appearance in The Colour Of Magic, and with his point of origin being the Counterweight Continent, could have been easily dismissed as slightly poor joke in a book chock-full of wonderful satires.

However, Pratchett applied a similar scattergun approach to Interesting Times. He included a range of gags and cultural references from nearly every culture in Asia, rather than focusing on just the Chinese, which would have been ample for his purposes.

To a casual reader, though, he appears to be doing little harm: he features callous and insensitive villains who run roughshod over the meek and downtrodden general populace, as do nearly all fantasy villains, frankly.

But the issue arises from the slapddashedness (if that’s a word) of the worldbuilding. By simply pushing together a bunch of stereotypes from all parts of the region, it merely feels like we can’t take it seriously. Fortunately, it is only played for comedy rather than any kind of malice, which does deflate the negativity a fair bit. And Pratchett was, I believe, aware of this: in an interview he made a throwaway comment about how this book was originally going to be called “Imperial Wizard” before realising that it might only sell in certain markets in America’s Deep South

But there is a lot to take seriously in this book. The revolution that Rincewind finds himself a part of threatens to be just as bad and unrepresentative as the regime they are overthrowing, and that’s something that a lot of literature doesn’t want to investigate too closely.

Needless to say, I do really enjoy this one, even with the reservations I outlined just now. It is funny, fast and filled with interesting characters and situations. But it was also the last time that I really thoroughly enjoyed a Rincewind novel: he was originally written as being a coward who kept getting placed in situations where he had to be heroic against his will and there were a few moments in this novel where the mask was starting to slip and Pratchett’s frustration at writing a decent, original way for him to become an accidental hero was becoming quite obvious. It’s no coincidence, I think, that he only appears in one more novel as a main character before becoming a guest character in other people’s stories.

Coming Up Next: Granny and Nanny find themselves becoming part of the social elite as they go undercover at the Opera in Maskerade.