Earthsea is an archipelago made up of dozens of islands. The inhabitants enjoy a mostly quiet, but sometimes hard, life They also enjoy a healthy respect for the wizards who live among them. One of those wizards is Sparrowhawk, who rose from humble beginnings on the island of Gont, before travelling to Roke and learning magic at the school there and went on to become one of the chief figures of his age and in Earthsea’s history.

Earthsea was the creation of Ursula K. Le Guin (1929 – 2018), one of the key figures in speculative literature (that’s Fantasy and Science Fiction for most of us) of the last seventy years. She is most famous for the Earthsea novels (hereafter referred to as the Earthseaquence) as well as The Left Hand Of Darkness, The Dispossessed, The Word For World Is Forest and the much-anthologised short story “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.”

Her writing tackles philosophy, feminism, politics and anthropology, but in a way that also keeps you entertained by the thought-provoking stories she tells as well.

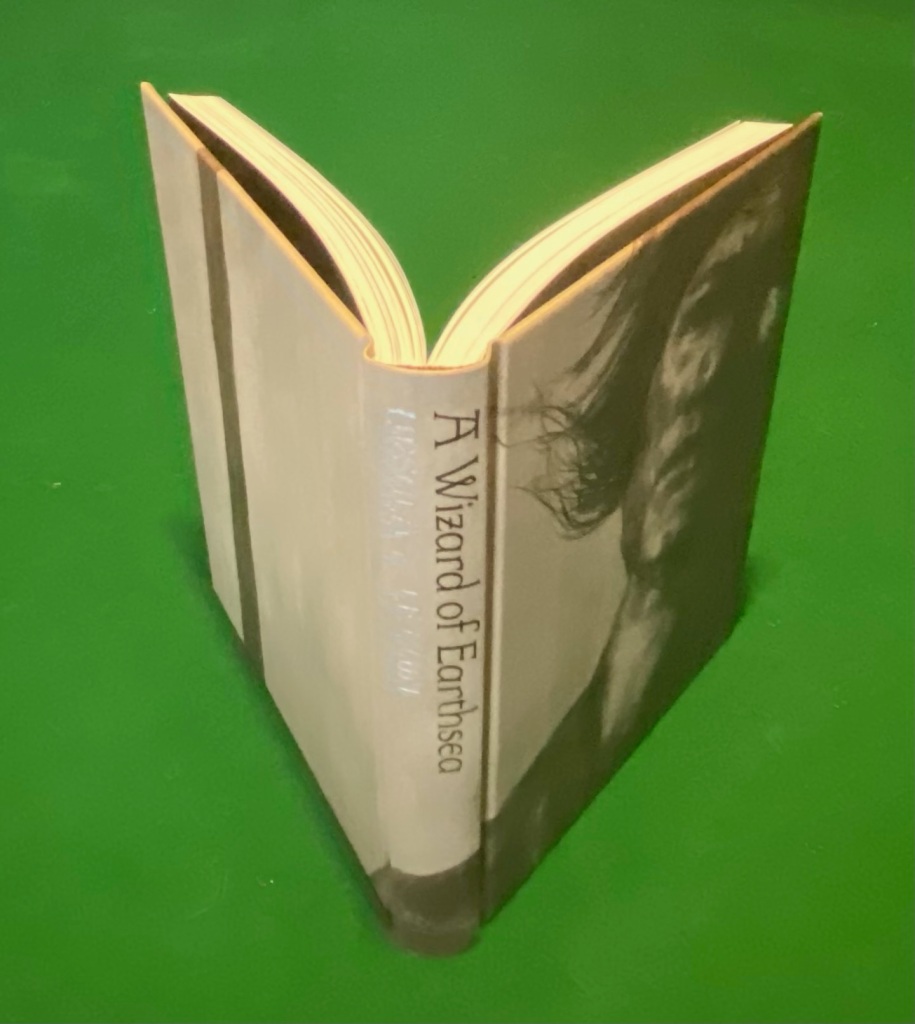

Like many people, I came to Le Guin’s work through A Wizard Of Earthsea (1968), the first novel of the Earthseaquence. Initially I didn’t think much of it but I loved the idea of the archipelago and travelling from one place to another by boat. We lived on the shore of the Derwent River in Hobart at the time and I loved going out in our dinghy and being on the water. I also had fond memories of ferry rides across the river to the city during the time that the Derwent Bridge was under repair after a cargo ship collided with it in 1975. Hobart is also the finish line for the annual Sydney-Hobart Yacht Race which roughly coincides with the New Year as well. I haven’t retained my fondness for boats since then but I do remember them vividly.

I came again to A Wizard Of Earthsea during my teacher training while doing a course on children’s literature. I’d read the other two books by then and enjoyed them immensely but I’d never returned to that first one. The thing that really struck me on this reread was the hefty mythological feel of it. The actions and words of characters carried the weight of significance and meaning. The events mattered, and unlike a lot of writers, Le Guin didn’t seek to undermine or downplay them with pithy one-liners or sardonic asides. Her characters took things seriously when they needed to. It also took a slightly different approach to magic than I was used to as well: a wizard was defined by what magic he knew, rather than what he did. In Earthsea, magic changes the world, and not always for the best, so a good wizard learns to be wise and circumspect in what magic he uses and when he uses it. It was an interesting idea and one that turned the Earthsea books into something a little more real to me, a place where magic could happen but where problems were more likely to be solved through labour instead. I’ve since become a reader who prefers a more judicious approach to the supernatural in my fantasy, so that may well have started there.

There was also the idea of names having power. Each person in Earthsea has a “use-name”, by which they undergo their everyday life, and their “true name” which is only known to those people an individual trusts. Also, until they are recognised as an adult, most people go by a “child name.” When someone knows your true name they have power over you so it is a gesture of utmost trust to be given someone’s true name. As an example, Sparrowhawk’s true name is Ged, while his child name was Duny. It’s a theme that plays out across the original trilogy and is also given some heft in the second set of books as well.

The second book, The Tombs Of Atuan (1970), was one that I read not long after I had first read Wizard. I remembered not being all that pleased by it at first because it was starting in a different place from where Wizard had left of and with a different character as well: Tenar, a young woman who is held to be the reincarnation of a high priestess in an isolated temple.

But it had a maze in it. I had a bit of a thing for mazes at the time and I loved that there was a picture of the maze in the front of the book so that you could follow Sparrowhawk and Tenar’s journeys through it.

Tombs is the shortest of the books, but it became one of my favourites. Ged and Tenar’s experiences on Atuan also flavoured a lot of my tastes in literature: for a long time afterwards, I became quite enamoured with stories of stark and austere religions that only partly lived in the real world; where life was harsh, but the promises of some mythical future were glorious; and where pitiful acts of rebellion were crushed by overly-zealous underlings who were the real powers behind their thrones. If they included the pitiful lamentations for a time past when “things were better for us” that was just the icing on the cake for me.

Tombs stood out for me as well because the main character was a girl. Fantasy in the late 1960s, when this was written, was mostly about boys. There were female characters, but they were mostly “prizes” to be awarded to victorious male heroes; love interests who took very little part in the plot.

Le Guin has said repeatedly that this was a conscious choice on her part, largely because there were almost no fantasy novels with female main characters at the time and she wanted to redress that. There were, of course, some exceptions – C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, for one (a set of stories written in the 1930s), Joanna Russ’s Alyx (stories written contemporaneous to Earthsea) and Anne McCaffrey’s entire oeuvre were stories with women as their focus – but very few of them were main characters telling the story from what was their point of view. Fortunately, things changed a lot during the 1970s and 80s for female characters.

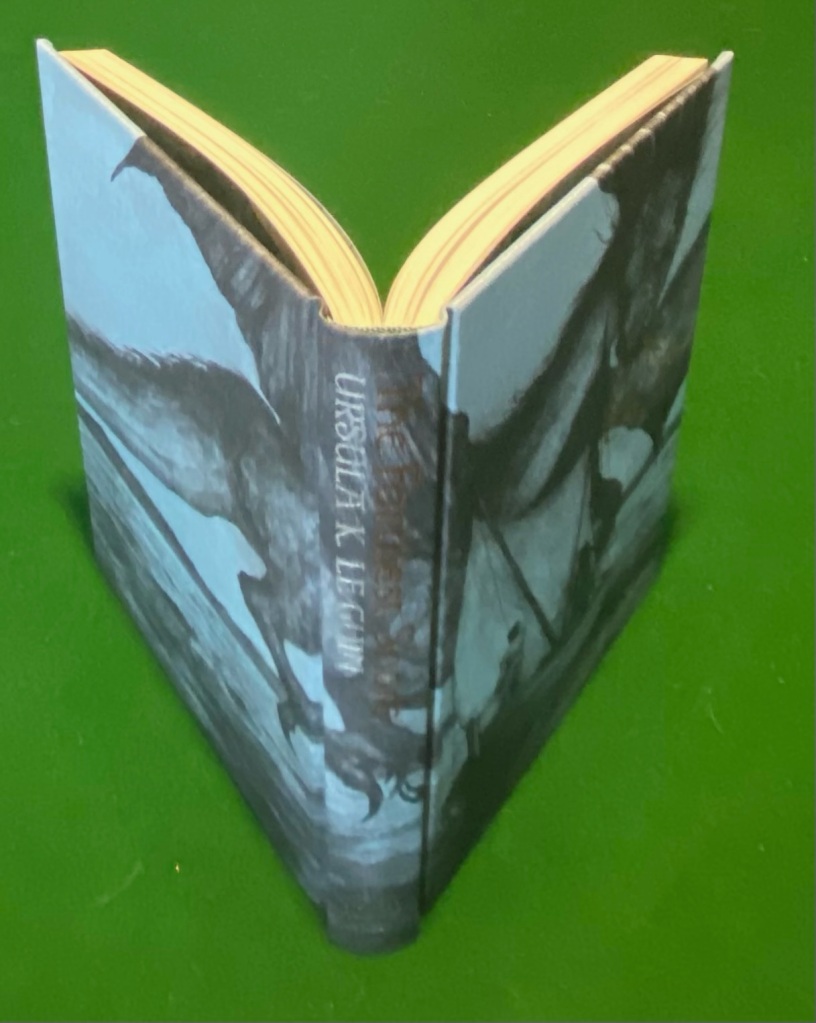

However, it was back to business as usual in the third book, The Farthest Shore (1972). This book again features Sparrowhawk as a character we only see through the eyes of others, this time through the point of view of Prince Arren. The message Arren brings is that magic is dying and that wizards and witches are no longer able to cast their spells. Sparrowhawk and Arren set out to investigate…

This was the first of the books that I actually had a copy of. I bought it when I was about 12, after having read the first two books in the series courtesy of my school library, and for a long time it was the only one of them that I read. It featured swordfights, slavers, taverns, dragons, spells, sailing – all things I was coming to associate with what was “important” in a fantasy setting (hey, I was 12) – and it told a story with the fate of a world at stake.

I loved it: Arren seemed to be an inexperienced but sensible protagonist, who was in awe of Sparrowhawk but tried to serve him as best as he was able. Sparrowhawk, on the other hand, was different to what he had been in the earlier books. However, it was twenty years later, and even at 12 I knew that people changed over time.

But best of all was the map at the front of the book. Maps were an integral part of my reading at the time: as with Tombs, I loved following the journey that Arren went on with Ged and it was fascinating seeing them travel across all the corners of Earthsea in search of the cause of the mystery of what was happening. It was only when I was older that I realized that Sparrowhawk (and Le Guin) may have had a higher purpose in taking Arren across all the places of what used to be a united realm before crowning him as the king of it…

But for many years, that was it.

Three books.

A trilogy.

Just to highlight this, for a long time my only reading experience of the book was as an omnibus trilogy that I found in the $1 box at a secondhand bookstore (this was years after The Farthest Shore was misplaced in a house move). It was creased and old but I snatched it up, took it home, covered it so it would last longer and it was my treasured copy until it literally crumbled to pieces in my hands.

Trilogies, as you probably know, became the standard by which fantasy series were measured throughout the 70s and 80s. It made sense: a beginning book, a middle book and an end book. Of course, the more cynical commented that it may well have just been people trying to cash in on Tolkien’s The Lord Of The Rings trilogy (but that was only a trilogy because of paper shortages: Tolkien wrote it and submitted it as just one book). And except for the fact that there are just as many single books or quartets and quintets around the place in fantasy as well.

Trilogies just sound cooler, I think… and there is some truth to it because there were a lot of “Tolkien-esque” fantasies that billed themselves as trilogies in homage to that masterpiece.

There weren’t a lot of books that set out to homage Earthsea, however. For a long time it was regarded as a classic of children’s literature, despite it not really being that at all: Ged is only a child in the first part of the first book, and then he becomes a fairly typically-aged fantasy protagonist for the rest of it. In fact, Tenar and Arren are also fairly typically-aged fantasy protagonists as well. So why were they regarded as kid’s books for so long?

Well, the publisher might have a fair bit to do with that: in the UK and Australia, they were published by Puffin, the children’s literature imprint of Penguin. And the themes of the books – growing up, showing maturity, dealing with adversity – are all admirable themes for children’s literature as well.

So what changed?

Well, the fourth volume changed how people viewed the entire series.

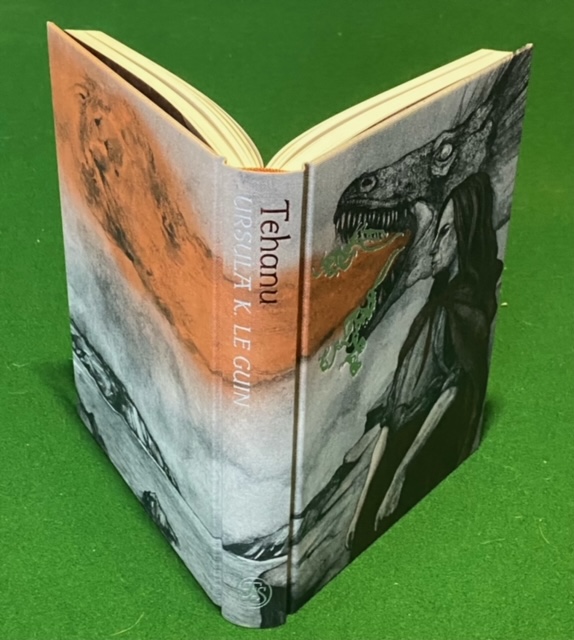

Tehanu was published in 1990, a full eighteen years after The Farthest Shore. Set during and after the conclusion of that book, it’s the story of Tenar, living on the island of Gont, in Sparrowhawk’s old village. She has gotten old, having married, borne children and become widowed. But she comes across two injured people who need her help: one is a child, seemingly abused and tormented by her family; the other is Sparrowhawk, who has washed ashore in his boat, sick and seemingly without his magic.

Tehanu is an astonishing book. It features very little conflict and the only fantastical events happen offstage and (spoiler alert) during the climax. But it is a wonderful achievement in fantasy.

For one thing, most of the characters are female. And most of the action is domestic in nature. Tenar is a widow in this book and a lot of what happens to her is fairly typical of many “women’s stories” in our recent past. She has become almost invisible, largely because her husband has died and she has aged. Her sons are regarded as being the head of the family now and they are either not present, having sought out a life away from home, or having better things to do than look after their parents property and maintain it. So Tenar finds herself largely at the whim of a society that tries to brush people like her under its metaphorical carpet.

Unbelievably, this sort of story had hardly ever been told before in fantasy. I mean, the genre is full of widows or old women eking out a rough existence on the fringes of society – but almost never with one as the main character. It was an almost revolutionary act in a genre that thrived on characters being young and virile.

I remember reading Tehanu for the first time and thinking that it was different to the other novels in what was then a quartet. Part of me rationalized it as being a book written by someone who was eighteen years older than when they had written the last book in the series, but a bigger part of me knew that this was a different sort of fantasy to the last book. Magic didn’t play a huge part in this book; nor did travel – in fact, the map in the front of the copy I had for many years only features the island of Gont, where all the action takes place.

It would have been easy to write this book off as a feminist revision of the Earthsea story except for one key fact: it was the original author writing it. So I accepted it as being a different sort of story – as the other three books had all been different sorts of story – and continued to enjoy it as a cornerstone of my reading.

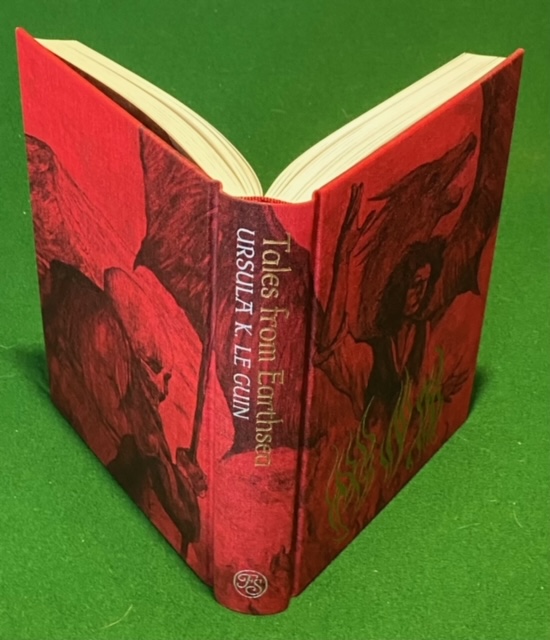

Then, in 2001, came the fifth book, Tales From Earthsea. This was different from the previous books because it was an anthology. Le Guin had been quietly writing a heap of short stories set in Earthsea since Tehanu and now they were collected together for the first time. It wasn’t all of them – there were a couple that had been written in the years before and during the original trilogy that hadn’t seen the light of day in decades – but it is pretty comprehensive.

The stories reach back into the earliest history of Earthsea and also stay in its present as well. It also features an essay entitled “A Description Of Earthsea” which details some of the history and geography of the archipelago.

Also in 2001 we were given the final novel, The Other Wind. In this story we get some proper closure for the Earthseaquence, in that there looks to be a true peace settling upon Earthsea with Arren, now King Lebannen, seeking a bride and the wizards closing the last barrier to true magical harmony in the archipelago. It’s a rather lovely book that gives just about everyone we’ve met previously a final moment to their story.

But, of course, it wasn’t the true end.

That came in 2018 with the death of Ursula Le Guin. However, in the years leading up to her death she had been working on a definitive omnibus of the Earthseaquence with acclaimed illustrator Charles Vess. When it was published we had a final gift in the form of “Firelight,” the last story of Ged, for which you will need a hanky.

The Books Of Earthsea, as this omnibus is known, is a beautiful artifact. Vess’s illustrations are wonderful and bring the story even more to life. It’s also the only place (so far) where the entirety of the series – novels and short stories – can be found together, which makes it invaluable for a fan.

There have also been adaptations. In 2004 and 2006 there were two screen adaptations that were somewhat less than successful. In 1996 the BBC produced a radio play starring Michael Moloney and narrated by Dame Judi Dench which is quite lovely to listen to. In the 1970s there was also a film version of the first two books written by Le Guin and Michael Powell (of Peeping Tom and The Red Shoes fame) which was never produced but which you can find the script for online.

For me, though, you can’t go past the movie in your head that comes straight off the page.

Earthsea was also one of the first non-European fantasies I ever read. By that, I mean that it didn’t take its inspiration from the myths and legends of Europe as almost all fantasists had done since the dawn of the genre. Earthsea is an archipelago and it is quite temperate in climate. Very few of the islands experience what we might call “cold” weather, save the islands large enough to have a mountain range to influence their climate at its higher points. So I always envisioned the inhabitants as being somewhat Polynesian in appearance, despite their being references to fishing villages and coastal towns that my mind’s eye pictured as being quite Mediterranean in construction. It was a mix that younger me was able to reconcile quite easily, despite it now making me quite queasy at the potential geo-political implications.

However I viewed it, though, the Earthseaquence remains as one of the seminal texts of fantasy literature and a firm favourite of my own.

You can find out more about Ursula Le Guin at https://www.ursulakleguin.com/